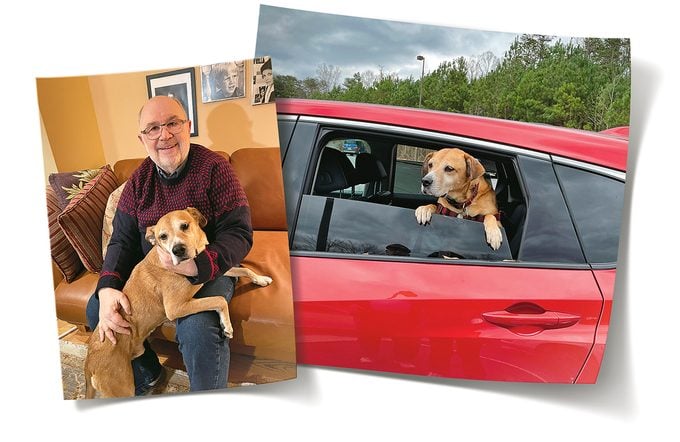

I Adopted My First Dog at 65, and Everything Changed

At first I didn’t think of Casey and me as “us.” But before long I found myself speaking of the things we shared.

When my husband talked me into rescuing a dog a few years ago, I worried about the downside: fur all over everything, arguments over walk duty. The time for a dog was decades ago, when we had a son at home to play fetch. At 65, we should be planning our next trip overseas, but Paul had always wanted a dog. For love of my husband, I said yes. But I doubted I could love any dog, much less the only condo-friendly dog on offer, a ragged-eared mutt.

He had a great story, I’d grant him that. Born unwanted in Ohio, taught to sit and stay in a prison where incarcerated people train pups for adoption, then sent to a shelter where he waited for a home until he was spirited away to Toronto by a band of volunteers dedicated to saving dogs from death.

We named him Casey. The first thing he did after galloping into our home was drench a chair with pee. He sniffed every corner and finally came to rest with his warm muzzle on my thigh. Maybe I could love him after all.

Our First Walk

On Casey’s first morning I briefly forgot we had a dog. I padded out of bed, fuzzy with sleep, to find another creature sprawled on the TV couch. This had happened a good many times before, but in the past that creature was my husband, sleeping in the very spot where I meant to lounge with my second cup of coffee and the obituaries section of The New York Times. Paul sleeps best anywhere but the bed, and the TV tends to get him nodding in the small hours. The presence of a dog—our dog—was a marvel. Oh, yes. It’s you.

Casey seemed to have expanded since the three of us had curled up with Grey’s Anatomy, two to watch and one to snore. In his languor, he pretty much filled the space, limbs every which way. His torn ear pointed straight up; the other flopped off the couch. I perched on the ribbon of space he’d left me and stroked his flank. Up went all four paws, his way of wishing me good morning. And a fine morning it was, with Casey in it.

My ideal morning involved leisurely online perambulations in my bathrobe. At least it had until this day. But Casey needed his morning walk, which fell to me as the resident morning person. I couldn’t be late, or he’d have an accident.

Everything we knew about Casey we’d learned from his foster mom, Liz, who handed him over to us. She said I should take him out right after breakfast. Liz had a fenced backyard; all she had to do was open the door. Then she could hang out in her pyjamas if she chose. Maybe make some muffins, do a crossword, call her mother. But Paul and I lived on the eighth floor of a downtown Toronto condo building. For me, Casey’s morning routine required lipstick, eyebrow pencil and presentable attire.

I’d laid everything out the night before—jeans and sweater for me, poop bags and liver treats for Casey. His crimson leash hung on the coat stand. I remembered Paul’s first attempt at walking Casey, the circular stagger outside Liz’s house. I was in for a challenge with this bruiser. Whoever trained him knew something Paul and I didn’t.

In my days working in publishing, I used to pull creative people into line. No, you can’t leave work when we’re in crisis mode, summer hours be damned. You want to misspell a headline “because it looks better that way”? Go back to fourth grade.

After all the humans I’d tamed, how hard could it be to walk a dog? People did it while texting, hauling groceries and easing strollers over snowy curbs. The bolder ones did it on skateboards and bikes, and my neighbourhood’s fastest canine, a shepherd mix in an orange vest, scurried alongside a man on a scooter. Clearly, anyone could walk a dog—you didn’t even have to be ambulatory.

This morning, we’d barely set out when a call rang out from behind, followed by a burst of laughter: “Who’s walking who?” Good question. We couldn’t seem to find our rhythm. Every few paces, a standoff ensued. My will against Casey’s nose.

That nose. Low to the ground, sweeping the air, pulling us forward on a full-tilt quest for anything that smelled edible. Down in one running bite went the soggy pizza crust, the nub of chicken in the gritty remains of its batter. Casey dragged me where the nose commanded, shoulders pumping. The exquisite precision of his nose recalled a hummingbird skimming a flower, yet the prize it sought might be the bloody feathers of a crushed pigeon or vomit from someone’s drunken spree. No relic of a living or once-living creature was unpalatable to Casey.

When not engaged in the quest for food, the nose evaluated spots for a pee. Casey zipped across the sidewalk like a daredevil driver cutting through three lanes of traffic, and came to a lurching stop at the hydrant summoning his nose. There he checked the accretion of canine pee that proclaimed to the neighbourhood dogs, I was here! He took his sweet time while a yellow rivulet spilled over the sidewalk and into the street. No matter how lavish the spray, he always had pee in reserve for the ritual known as marking.

I thought I knew what it meant to walk my downtown neighbourhood. Check out the movies playing at the local theatre. Take note of a shoe sale, a new wood-oven pizzeria. Eavesdrop on conversations. All the while setting a pace, getting my exercise while my mind floated free. Walking was my gateway to an inner world in which I chose where to direct my attention.

Not with Casey. I veered between meandering, waiting and a fair approximation of a drunken shuffle, both hands gripping the supposedly handsfree leash that looped around my waist (the dog walker’s equivalent of training wheels). Paul and I had a plan for Casey’s walking, an hour a day from each of us. Why had I worried about Paul holding up his end, when I was the slight one trying to stay on my feet?

Pedestrians swerved to avoid us; hazards loomed on every block. Casey tried to chase cars that looked wrong for unfathomable reasons (just when I thought it was only orange cabs that set him off, he’d charge a black minivan).

And that was the easy part. Squirrels sent him into warrior mode, with head-turning ululations and acrobatic leaps that nearly knocked me to the ground. Before Casey, squirrels reminded me adorably of Beatrix Potter’s Nutkin. Now they seemed more like battle-hardened ruffians on Game of Thrones, a tribe of them always ready to burst from the nearest sapling.

While flying at a squirrel I hadn’t seen in time, Casey ran smack into a couple of pedestrians. The woman flashed a tolerant smile; the man scowled at me over his shoulder. At the rate we were going, someone might get hurt. Come to think of it, my shoulder was hurting already. I’d heard of strength training for golf and skiing, but dog walking?

I checked my watch. Five more minutes and we’d finish the hour. We. The right word for Casey and me on the couch, gazing into each other’s eyes.

Out on the street there wasn’t any we. Intellect against instinct, that’s what there was, intellect being the loser. We couldn’t make it home fast enough.

Just as I let my guard down, Casey had a set-to in the lobby with a neighbour’s Lab, Betsy, infamous for roving the halls at night. Her owner looked us both up and down, lip curled. “Rescue dog?” To lighten the mood, I mentioned Casey had spent his puppyhood in prison. “You’re brave,” he said, pulling Betsy away from my jailbird.

The elevator seemed to crawl to the eighth floor. Casey ran to Paul’s arms for some vigorous rubbing and the question that cannot be asked less than twice, with escalating volume: “Who’s a good boy? Who’s a good boy?”

“Casey! Casey!”

We had a good boy alright, but it soon became clear that we’d both have to up our walking game.

Paul got into trouble at St. James Park, beloved for its gazebo and landscaped gardens, when Casey had a noisy meltdown over a squirrel. A tweedy codger shook his finger at Paul. “That dog of yours is a nuisance. Don’t you realize some of us come here for a little peace and quiet?” He pointed to a wisp of a dog perched on its owner’s lap like a stuffed toy on a satin pillow. “That’s how a dog should behave. And until your dog gets the message, I suggest you keep him out of this park.”

The night after Casey was exiled from the park, he lay on what we already called “Casey’s couch,” twitching as he snored. I ran my fingers along the cleft in his skull, where his ginger fur darkened to rust. I’d never know for sure what Casey dreamed, but I figured a squirrel was involved. Go, Casey, go. Run the varmint down.

A dog trainer, Laurie, soon paid us a house call. She looked younger than our daughter would be if we’d gotten around to having one, but dog people on Yelp said she knew her stuff. I’d told her to expect a squirrel-crazed, trash-chomping rescue mutt, billed as a Lab/pug mix, although who could say for sure?

Laurie was sure. “He’s all hound.” With that pointy snout, he couldn’t be anything else. And this explained a lot about our would-be squirrel assassin. Like every hound who ever chased prey, Casey was designed for the task, with a nose that ranks among the wonders of the animal kingdom. His “squirrel attacks,” as we called them, expressed his greatest gift. Some dogs were born to bark at strangers; ours was born to hunt rodents. I figured we had the better deal.

Laurie put Casey through a few paces. He sat, stayed, lay down as he had been taught in prison—and as he’d do for us if we learned to speak his language. “You lucked out with this guy,” Laurie said. “He wants to please.” He could have fooled me, but Laurie was the pro.

The three of us took Casey to a free-and-easy park where teens shoot hoops and no one would get fussed about a ruckus. The idea was for Laurie to watch Casey do his worst, and as we neared the first squirrel-inhabited tree he rose—no, soared—to the occasion with his full repertoire of sound effects while I, the clueless human at the end of the leash, stood and bleated, “Casey, stop!”

I half-hoped Laurie would exclaim at his antics. If Casey had to raise hell, let him be the loudest, most epically acrobatic hell-raiser she had yet seen. How many squirrel-chasing dogs do back flips, then jump up to try again? For him the leash did not exist, nor did failure. Every squirrel was a promise of victory. Casey was my Don Quixote charging at windmills, my pratfalling Buster Keaton.

Laurie watched the show with her hands in the pockets of her hoodie; she’d seen every move before. “Like I said, all hound. You want his attention on you, not the squirrel. That’s going to be your challenge. So let’s get to work.”

The Lauries of this world don’t really train dogs. They teach perplexed humans to stop doing what doesn’t work and acquire more constructive habits. Laurie reminded me a little of Annette, our couples’ counsellor back in the striving years. Whatever long-forgotten muddle we were in, she’d seen it all before.

How hard we’d worked with Annette in her basement office with the pine-panelled walls. How thoroughly we’d prepped for every session. If she’d given marks, we’d have aced her course. “You’re remarkably well-matched,” she once told us, peering through the enormous glasses women wore in the days of shoulder pads. “It’s a miracle that you found each other.” Her version of Laurie’s “You lucked out.”

With Annette, Paul and I tuned in to the sometimes mystifying but basically well-intentioned people we were at heart. We were about to begin the corresponding process with a dog, who had never forgotten a birthday, stormed out in a huff or blamed either of us for a thing. Compared to making a marriage, training a dog should be a snap.

I wasn’t getting through to Casey, Laurie said. My entreaties were meaningless noise, a sound soup of his name and half-hearted marching orders. Nature gave Casey a mission: slaughtering creatures who, in his mind, had no right to exist. To interrupt him, I’d have to make some noise.

I had three options: whistling, shouting or a vigorous hand clap. I never learned to whistle, and clapping is no good with gloves on. That left shouting. As squirrel after squirrel romped by, I tried to summon a respectable shout: “Casey! Casey!” How could it be that the name I loved to murmur was so hard to shout with conviction?

Paul shook his head (in our class of two he was the star). Shouting had always come easily to him—too easily for my liking, but with dogs it served a purpose. “More authority,” he said. “More volume.”

The authority part I could nail. At 65 I’d damned well earned the right to be a feisty old dame. I demanded refunds with aplomb (and got them). I told wait staff not to call me “dear” and shambling 20-somethings to make room for me on the sidewalk. I complained and corrected with ease.

But nobody loves a woman who shouts. In my childhood home it was well understood that only my father had the right to shout—and he could erupt without warning. Sober, he quoted Yeats to my sister and me at bedtime. When we modelled new outfits, he would bow to us and ask, like a gentleman from an old movie, “May I have your telephone number?” (Telephone: an old-fashioned word, even circa 1960.)

But when he was drunk or hungover, the smallest thing could get him going, like the double boiler for his oatmeal. “What’s become of the blasted thing? Is this any way to organize the kitchen cabinets?” The rest of us would wake to a percussion band of clatter. And I’d know in the pit of my stomach that the day ahead was going to be a stinker.

Fear had a sound: shouting. What I feared was not so much my father’s anger as my own. Because he was a man—the man of the house, in the language of those times—he got to blow off steam. Because I was a girl, I didn’t. I should keep my head down, stay out of Daddy’s way, do my best to placate this overgrown baby in the guise of a man.

Now I had Laurie’s permission to shout. More than that, I had marching orders. For Casey’s sake, I would learn to let it rip.

Us-ness

After our first session with Laurie, I walked Casey with her voice in my head. I practised shouting, “Hey!” when Casey jumped into predator mode. The pavement didn’t split and swallow me up. I sounded loud and proud. Better yet, Casey started to get it—not every time or even half the time, but often enough, especially if I followed “Hey! Ca-a-a-SEY!” with a sharp tug on the leash. Then the treat, then the neckrub. “Good boy,” I would say, as Laurie had taught me.

I was asking a lot of Casey. In the presence of a squirrel, he was anger incarnate. His eyes blazed; his hackles rose. I thought hackles were only an idiom until I saw the band of rage down Casey’s back, where his fur is darker and coarser. When they stiffen, he looks bigger, more threatening, as nature intended. He was an officer of the laws of nature, determined to wipe lesser creatures from the earth. One squirrel affronted him; a bobble-headed flock undid him.

Anger consumed him quickly but vanished with the squirrel. Casey’s anger had an urgent purity. Unlike any human I’d known, he didn’t hold grudges. He wouldn’t ruminate on what he could have done to that squirrel if not for me, the spoilsport clutching the leash.

Casey and I walked together as a biped and a quadruped, an aging woman and a young dog, a second-guesser and a creature of impulse. One who cleaned up, one who drooled on the floor. One who compared recipes for roasted Brussels sprouts, one who had to be restrained from licking barf off the sidewalk.

It was our differences that held my attention, rather than the shared pleasure of the outing. Casey had his world, I had mine, and therefore I didn’t think of him and me as “us.” But before long I found myself speaking of the places I shared with Casey—our places, mine and his. The mural where I posed him for a shot, the park where we made friends with a juggler practising his moves.

I was beginning to understand who we would be to each other. We were Us now, and it was enough. The unlikeliness of our comfort together magnified the joy of it. As long as squirrels roamed the streets and parks of Toronto, there would be passing bursts of anger that didn’t change a thing. What we had, as a woman and a dog, underscored the miracle of any two fallible beings, committed to opposing points of view, planting the stake in the ground that is Us.

Paul will be Paul, Rona will be Rona. In the beginning came a you, a me. One who slept late, and one who equated purpose with rising early. One who left the marriage when our son, Ben, was a toddler, saying, “I never loved you” (me, exhausted by my young marriage and younger child), and one who said, “It’s not over. Let’s try again.” One who knew what things should be, and one who didn’t get it (actually, that would be both of us). From differences and disappointments, we created Us. And as Us, we brought Casey home.

Us-ness, once you’ve found it, can accommodate a fair bit of tension. Some days I couldn’t stop Casey from charging at squirrels number one through 17, but he calmed down by squirrel 99. With a multitude of squirrels about, we always had another chance. I arrived at a grudging respect for the squirrels, who would stare Casey down with what looked to my human eyes like amusement.

Squirrel by squirrel, day by day, we started to find our groove. We sometimes walked entire blocks without incident, Casey’s tags clinking in time with my steps and his leash vibrating gently in my hand, now that I’d learned not to grip it. He knew every variation on our route. If I didn’t pick his favourite, he would tug, as if to ask, “You’re sure about this?” I was sure. A slight disagreement on the route was no big deal for a simpatico pair like us.

A Master of the Art of Sleeping

We were ripping through our value pack of poop bags. Casey was remarkably productive, often filling several bags in a single walk. I didn’t mind, though. Scooping gave me a chance to do one thing right every day. And the humble task literally grounded me.

It forced me to tend the cracked and mottled sidewalk, the sodden leaves at the edge of a walking trail. It was a bondage I shared with all dog folk who care enough to do the right thing. The woman bending from her wheelchair with practised caution, the elderly walker favouring a bad knee. The young parents exclaiming, as their toddler scooped for the family dachshund, “That’s it! Good girl!”

When I started walking Casey it was early spring, when receding snow exposed a winter’s worth of blackened excrement in every park. It clumped at the rims of hedges and dotted the sidewalks, a desiccated record of human can’t-be-botheredness. So many scoffaws about, making me a target for those who hold dogs in contempt. Some people hate dogs for jumping, others for disturbing the peace with their barking. What unites them all is their loathing of poop.

I’d just disposed of Casey’s first of the day when someone approached us with an open Clive Cussler novel in his hand and headphones blasting cacophony into his ears. As he passed, he yelled over his shoulder, “I hope it’s not your dog who just left his business on the sidewalk! It’s a pox on the city!”

The last time I’d heard the word “pox” used in the Shakespearean sense, I was trying to ace an English course. Full points to Mr. Multi-task for literary air, but his logic stung. He didn’t turn his head when I called, “Not us!”

Us. Any scorn directed at Casey is really directed at me. When you get down to basics, I was scooping because I loved him. I hoped my fellow humans would look benevolently on him, or at least not disdain him. Every time I bent for Casey, I proved that Yeats was right: “Love has pitched his mansion in/ The place of excrement.”

I no longer missed walking with Paul. Walking with a dog had distinct advantages. If Casey took any notice of my mood after a rough night’s sleep, he showed no interest in what this meant for him or when I might snap out of it. He still sauntered beside me, ears sliding back to catch a rustle in the grass no human could detect.

I didn’t have to earn the good cheer enveloping us. Its engine was Casey’s zest for the minutiae of his day—the stained wall that must be peed upon because no other wall compares, the postal clerk who must be greeted for a biscuit from her tin behind the counter. On Casey’s map of pleasures, I was like the earth and the sky, reassuringly present but not the focal point.

As Laurie had taught me, I crossed the street to dodge cats, darting toddlers, unpredictable puppies—anything that might flip Casey’s anger switch. He took exception to dogs off-leash (they made him feel insecure), dogs with enormous furry heads (not dogs, as far as he could tell) and a good many large black dogs (who knows why?). Meanwhile other dogs took exception to him for similarly unfathomable reasons. When I couldn’t remove Casey, I’d distract him by throwing a handful of treats about.

I knew we’d met a milestone when Casey had a full-throttle squirrel attack close to where we’d first walked with Laurie. Loud, proud and fast, I executed my three-step routine: the shout, the tug, the “Good boy.” Someone waved, a professional dog walker whose three charges were all sniffing the same patch of grass. “Nice work!” she called. How long had it been since I was asked, “Who’s walking who?”

One day I had a brainwave: Us-ness might serve a practical purpose. Casey has the enviable canine gift for sleeping anyplace he happens to be, from the back seat of the car to a friend’s yard. I have the human gift for rolling worries around in my brain when all I crave is sleep.

In the middle of a restless night, I went looking for a soporific book and found Casey zonked out on the TV couch. He didn’t stir when I sat down beside him to stroke the soft fur on his neck. He exhaled, sinking deeper into his rest. He sounded almost human, but then every human sigh is mammalian. Hey, Casey. Take me with you.

He’d left me just enough room to curl up and make his firm, warm chest my pillow. Unlike all other pillows in my life, Casey’s chest expands with his breath. His fur smells pungently of himself. No matter what he’s kicked up on our rambles or where he’s pushed his snout, he smells exactly as he does.

My headful of niggles rose and fell with Casey’s breath like a boat on a calm sea. I didn’t yet know I was taking liberties: a five-kilogram human head is a not-inconsiderable burden for the chest of a 14-kilogram dog, and any dog hates to be confined. But Casey was too far gone to throw me off right away. He supported me for about five breaths, enough to remind me how deep and slow a breath can be.

I’ll never paint like Matisse or write a poem like Emily Dickinson, but Casey let me believe that I could sleep like him, my personal master of the art.

For the sleep of my dreams, I’d gone to extraordinary lengths. Bought a king-sized mattress that adapts to my weight and body temperature, its materials developed by NASA. Followed a regimen of pre-bedtime baths and stretches. Taken heavy-duty sleeping pills. Consulted a sleep psychiatrist to help me kick the pill habit and learn the rules of “more efficient sleep.”

On a night of broken sleep not long after Casey joined us, I found him dead to the world on the couch. What he knew about sleep no human could teach me. Falling asleep, like falling in love, is about letting go of expectations, loosening your grip on control. I learned this watching Casey.

Sprawled or curled nose to tail, eyes shut or half open, he got the average dog’s 12 to 14 hours a day. All I asked was seven. With a little help from my canine coach, I had become a whole new sleeper.

It didn’t occur to me then that he could coach me better if he were in the bed, at my side. Roughly half of dog people sleep with their animals, but I’d made a rule—no dirty paws on our 300-thread-count sheets—and I was sticking to it.

I returned to the bedroom, where the sheets had cooled while I had been hanging out with Casey. My side of the bed looked like the shipwreck of my night so far—a tangle of sheets, eyeshades and layers of clothing added, then subtracted, in my search for the right body temperature. Paul’s side lay untouched while he slept in his favourite armchair.

I positioned myself on the neck-cradling pillow I need to take with me everywhere. The white-noise machine whirred. I replayed the moment Casey and I had just shared—his fur against my cheek, his breath lifting me—until I slipped into a dream of Us.

From the book Starter Dog: My Path to Joy, Belonging and Loving This World, by Rona Maynard. Copyright © 2023, Rona Maynard. Published by ECW Press. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Next, check out this heartwarming story about the bond between a woman and her Haflinger horse.