For 50 Years, This Ingenious Train Ferry Connected PEI to the Mainland

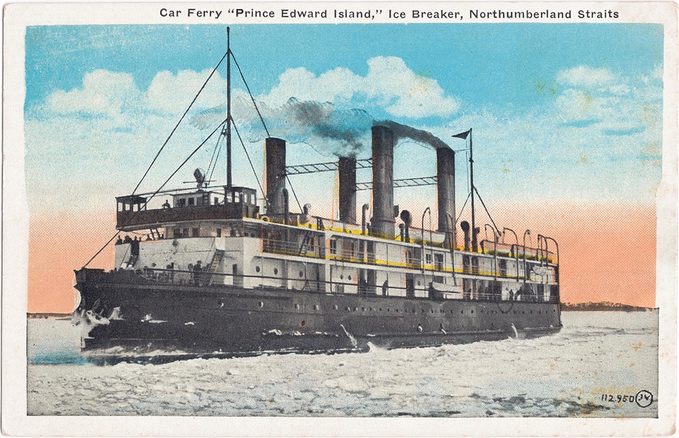

Christened the SS Prince Edward Island, it offered a new frontier for train and car travel.

In the early 1900s, automobiles were banned on Prince Edward Island and folks travelled mostly by schooner, horse and buggy, and train. But in 1917, there was a new development—a one-hour train-ferry service connecting the island to New Brunswick. Imagine—you could take a train to the mainland!

The SS Prince Edward Island arrived from the U.K. in 1915, but the ship terminals at Borden (later Borden-Carleton), P.E.I., and Cape Tormentine, N.B., weren’t completed until 1917. For Prince Edward Island to accommodate standard-gauge railway cars as well as PEI Railway’s narrow-gauge variety, a third rail-track first had to be built.

In October 1917, the SS Prince Edward Island finally made its maiden voyage across the Northumberland Strait. To load railcars onto the ship’s train deck for transport, they needed to be backed aboard; another train engine at the arrival terminal would then pull the railcars off, thus allowing passengers and cargo to continue on their voyages.

The train deck could fit a dozen standard-gauge railcars on its two parallel tracks. On either side of the deck were cabins that could accommodate 80 officers and crew. A galley that contained a lift to the pantries of the upper-promenade dining rooms—where passengers would convene—could be accessed from this lower deck.

The forward deck house offered first-class passengers a 38-seat salon, as well as a ladies’ room, smoking room and pantry. For second-class passengers, there was the after-deck house. Though similar to the ship’s first-class accommodations, its dining quarters seated 46, so there was slightly less elbow room. Still, all passengers were said to have found the experience comfortable and elegant.

Officers’ cabins were located just above the after-deck house.

In its first year of service alone, the SS Prince Edward Island recorded 506 crossings.

Memories of the SS Prince Edward Island

My mother-in-law, Edna Matthews, recalls boarding the SS Prince Edward Island in her hometown of Piusville, in the west end of P.E.I., travelling to Borden, and then crossing the often ice-filled Northumberland Strait to Cape Tormentine, N.B., before continuing on to Halifax. (Fortunately, the SS Prince Edward Island was designed to ride above the ice and crush it with its massive weight.)

Setting off on this new adventure at the age of 16, the railway ferry opened a new world for her. The year was 1943 and it was to be her first trip to Halifax—on the very train that had taken her brother Alyre away to war. She recalls with tear-filled eyes how the train had also brought him safely home, her mother running through a grassy field to embrace him as he disembarked.

Edna’s first rail-ferry ride was a breeze, but she also speaks of another that took place in a storm, dishes from the dining room flying from shelves and crashing to the floor. At the time, she was one of only two female passengers on board. The captain led the pair to the officers’ quarters and told them that under no circumstances were they to leave the room until the boat docked. When the captain finally returned to escort them back onto the train, he told everyone, “We won’t be going anywhere tonight.” The look of relief on his face was one Edna would never forget.

Ship, Rail and Auto

By 1918, the automobile was no longer considered “an instrument of death” on Prince Edward Island. The ban, which had been loosened in 1913, was fully lifted. The automobile was here to stay. By the 1920s, cars—and later, trucks—were regularly loaded onto flatcars for ferry transport aboard the SS Prince Edward Island. That is, until the early 1930s with the launch of the SS Charlottetown, a dedicated car-ferry steamship that—with its larger rail deck, circular drive, and room for 44 cars that could be driven directly onboard and off—took on the brunt of this service.

Auto capacity had been increased on the SS Prince Edward Island in 1938, but, at 40 cars, it still fell short of that of its rival steamer. The upgrade also resulted in a change from the ship’s original layout. The second-class facilities and officers’ quarters were removed to make room for the auto deck. This update also put an end to the two-class system of accommodations, though there were still faint reminders, notably an engraved plaque on the archway above a pair of staircases that read “Second Class Passengers.”

When the SS Charlottetown sank in 1941, the SS Prince Edward Island resumed its spot as the major car-ferry vessel in the area—and the only one that operated through the remainder of the Second World War.

End of an Era

But, as the old steamer had no circular layout to access its auto deck—unlike the SS Charlottetown—drivers had to back into narrow, tight spaces, which proved a bit inconvenient. In the 1940s, with a higher demand for automobile space, if the ship wasn’t transporting a full load of railcars, part of the ferry deck was planked between its tracks to fit more cars. Soon, capacity was increased even more with the use of rail flatcars to transfer autos. But by the 1950s, flatcar transport was phased out to allow more room for more vehicles.

In 1969, CN stopped operating passenger trains on Prince Edward Island altogether. Around the same time, the SS Prince Edward Island was retired, after a proud 51 years of service.

Decades later, 1986 saw the end of an era, with CN Marine renamed Marine Atlantic and the newly branded company soon removing all traces of its link to CN. By the end of 1989, CN itself had abandoned its rail lines on the island, with the last of its locomotives and railcars hauled away.

For unique historical images of P.E.I., go to peipostcards.ca.

Next, find out what happened to the original Bluenose.