Why I Tell My Grandfather’s Story Every Remembrance Day

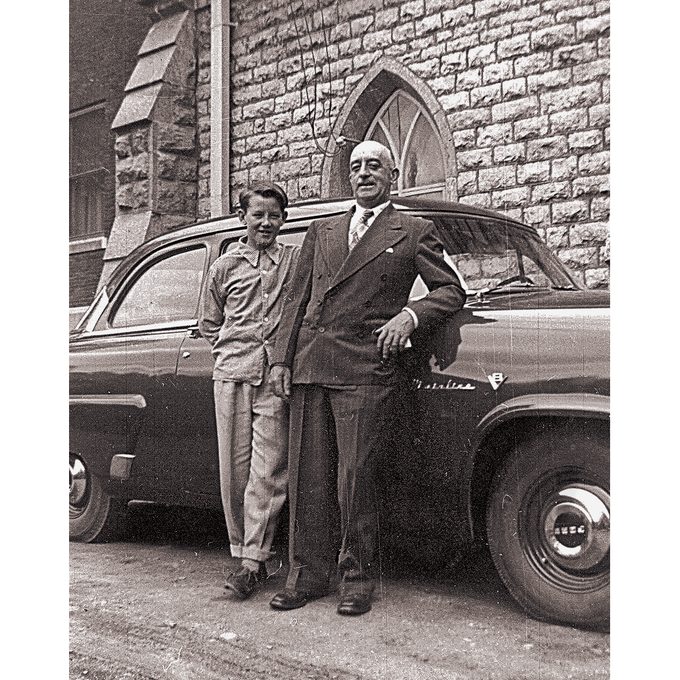

It’s not a matter of me being boring; it’s simply that I was and still am so very proud of my grandfather Vernon C. Clark—a very brief holder of the Victoria Cross.

In 1914, during the First World War, my grandfather Vernon C. Clark, like almost everyone 18 and older in those days, joined the Canadian Army to fight overseas. He was a small man and enlisted as a mechanic. When reporting for first line of duty, he mentioned that he was raised on a farm; he was assigned to the calvary because the line of thinking back then was: farm = horses. Horses were still used to move artillery in the Great War.

He was not pleased, as you could well expect, for two reasons: first, because he was a mechanic, not a farmer; and second, because the enemy would always shell the calvary first upon any major attack, as they sought to immobilize the artillery units during battle.

During one of his first stints of action, he was surprised to learn just how strong the attack of bombshells actually was, even after hearing all the stories. He fought in some of the biggest battles on the Western Front: Verdun, Vimy Ridge, Somme, and the battles of Ypres and Amiens.

Near the end of the war, as British and Allied forces slowly pushed back the German Army, the Germans made a surprise counterattack in hopes of delaying the Allied forces. The German artillery unit gave it all they had. Several shells landed very close to my grandfather’s unit; one even caused a piece of shrapnel to end up in his foot, something that would affect him for the rest of his life. He was taken to the infirmary, where it was confirmed his foot was so bad that he was proclaimed as no longer fit for duty, and subsequently sent home.

On the ship back home to Canada, my grandfather lay in the infirmary and was placed in a private area separate from all the other wounded. There seemed to be a nurse attending to his every wish. Many soldiers saluted him as they passed his bunk; he had no idea why. Plus, he was getting preferential treatment compared with the other wounded soldiers. This, too, was very puzzling to him. He was being given steak and wine with his meals and was always served before everyone else. No one was complaining about him being served first and he had a private nurse!

Finally, my grandfather asked the nurse why he was being treated like a king when so many others seemed to be much worse off than he was. The nurse looked at him like he was crazy and told him that this was the way they treated all Victoria Cross recipients.

You may be aware that the Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest military decoration that is or has been awarded for valour “in the face of the enemy” to members of the armed forces of various Commonwealth countries and previous British Empire territories. It’s the highest of all the orders, decorations and medals. It may be awarded to a person of any rank in any service, as well as to civilians under military command.

The name tag on the bed that my grand father lay in read “Vernon Clark—VC” in stead of simply “Vernon C. Clark.” Someone had made a mistake with the sign!

He quickly realized that everyone must think he had been awarded the Victoria Cross, and he also realized that he had hit the jackpot! Suddenly his foot felt a whole lot better.

But soon, his conscience got the best of him. If you ever knew my grandfather, you would know that he was a very honest man. During his tour of duty, he witnessed atrocities of war that you and I could not begin to imagine. He saw how so many of the other wounded soldiers on the same ship were much worse off than himself. So when his next meal arrived exactly on time, as usual, he owned up to this error to the nurse. He told her that the name tag was correct but that someone had made a mistake in adding “VC” to the end—he had not been awarded the fabled Victoria Cross.

The nurse looked very surprised but then began smiling. She told him that they were almost at their destination of St. John’s, Newfoundland, therefore no one needed to be the wiser. So my grandfather continued to have his steak and wine and to be saluted vigorously by many higher-ranking soldiers. And although his nurse was not as attentive as she had been previously, she would often pass his bunk and throw him a knowing wink.

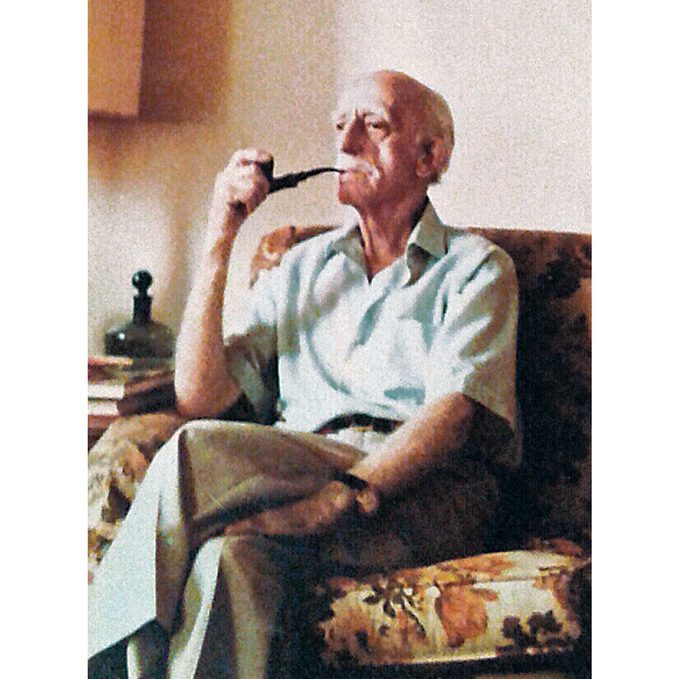

Vernon C. Clark lived to 94 years. As a result of that war injury, he had to wear a special shoe for most of his life. On his 80th birthday, he received the standard commemoration letter from then-Mayor of Toronto David Crombie, then-Premier of Ontario William Davis and then-Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, honouring veterans who’d fought in the great wars.

I have been telling this story every Remembrance Day since my grandfather, whom we called Poppa, first told it to me in 1974. (Of course, some of the details may have been slightly off, as there was a bottle of Dewar’s blended scotch whiskey on the table as Poppa told me the story.)

If you’re around me on the 11th of November this year, you may hear me retelling my grandfather’s Victoria Cross story once again. If so, please forgive me: It’s not a matter of me being boring; it’s simply that I was and still am so very proud of my grandfather Vernon C. Clark—a very brief holder of the Victoria Cross. I can’t begin to tell you how much I miss him, especially every November 11.

God bless you, Poppa.

Check out more Remembrance Day stories honouring Canadian veterans.