By Donating Their Children’s Organs, These Parents Gave Other Families Hope

“Instead of five families mourning the loss of their child, it’s only ours. That’s why organ donation is worth it.”

It’s March 29, 2016, and to Josée Scantland and Patrick Grondin, the sunlight pouring into the CHU Sainte-Justine pediatric hospital centre in Montreal feels brighter than ever.

Their five-year-old daughter, Élissa, is about to be brought out of the operating room after receiving a new heart. Outside the OR, the couple is bursting with joy as a TV camera zooms in. “Our daughter is going to live again!” Josée exclaims. “Thank you to the donor’s family,” adds Patrick. “We don’t know you, but you can be proud. You saved our child’s life.”

Some 200 kilometres away in Gatineau, just across the Ottawa River from the nation’s capital, Michel Carpentier and Danielle Lafrance are glued to the screen, moved to tears by the story. Just a few days earlier, they made the decision to donate the organs of their 23-year-old daughter, Emmanuelle, who died by suicide; they had found her lifeless body in the garage of their family home. “She was so sensitive and wanted to save the world,” her mother recalls. And so they chose to offer eight of her organs for transplantation.

Now, seeing Élissa’s parents so happy allayed some of their grief: In death, Emmanuelle had saved the lives of whoever had received her organs. What they didn’t know was that the heart beating in Élissa’s chest was actually their daughter’s.

The year she was born, Élissa Grondin underwent two open heart surgeries to correct congenital anomalies. She’d led a normal life until the age of four, when she was struck by a virus that damaged her heart. Confined to the intensive care unit of the CHU Sainte-Justine hospital, she spent seven nightmarish months waiting for a donor.

In the five weeks leading up to the transplant, she was kept alive by a mechanical heart and couldn’t leave her hospital bed. “The blood clots that formed in the tubes of the machines could have killed her at any moment,” says Josée. Convinced only a miracle could save their daughter, Élissa’s parents spent their days by her side and retreated to the nearby Ronald McDonald House to rest when they could.

Then, on March 28, 2016, just as it seemed all hope was gone, a doctor summoned them to a small lounge area next to their daughter’s room. Their prayers had been answered: A donor heart had finally been found. Élissa would be getting it the very next morning. Following whoops of elation, Josée and Patrick spent the hours before Élissa was taken into the operating room gripped with anxiety. “It was her last chance,” says Patrick.

Eight hours later, the transplant was deemed a success.

In 2021, 409 patients of all ages in Quebec received a transplant—thanks to 144 individuals, only four of whom were pediatric donors (those under the age of 18). Each year, the names of roughly 15 kids are added to the transplant waitlist, and around the same number get a new lease on life, since one deceased patient can donate up to eight organs.

“On average, children under five have to wait more than a year for a heart transplant, as their condition grows increasingly critical,” says Dr. Marie-Josée Raboisson, cardiologist at the CHU Sainte-Justine. Often the only way to keep them alive is to temporarily implant a Berlin Heart ventricular assist device (VAD), but there are risks involved, and it isn’t always an option for patients with malformations.

“About half the parents of deceased children decline to donate the organs, often because they don’t want the body to be cut up,” says Dr. Matthew Weiss, medical director of organ donation at Transplant Québec and a pediatric intensive care physician at the CHU de Québec. “The reality is that the surgery is performed very respectfully.”

All pediatric hospitals have trained nurses whose role is to reassure families and provide them with information about the circumstances (brain death and cardiac death) that made the donation possible, and about the retrieval of organs. They explain to consenting parents that the child’s body will remain on artificial support in the intensive care unit for a few days while compatible recipients are found.

“In some cases, the wait can become unbearable, and the parents change their minds,” adds Weiss. “They are devastated, and they need time to think,” acknowledges Dr. Saleem Razack, former director of pediatric critical care medicine at the Montreal Children’s Hospital. “Others refuse owing to their religion or beliefs.”

Still, those who consent are unanimous in their conviction that helping another child heal while experiencing such a profound loss is the most meaningful choice they could have made.

Maxime Lapointe Bélair and his wife agree. Their four-year-old daughter, Raphaëlle, passed away from a respiratory infection at the CHU de Sherbrooke on February 23, 2019. When she was declared brain dead, a nurse suggested they might want to speak with Marie-Pier Savaria and her husband Benoît Lefebvre.

After Marie-Pier and Benoît’s eight-year-old son, Justin, drowned in a Sherbrooke pool on June 17, 2017, the couple went on to create a foundation that encourages organ donation. “It doesn’t solve everything, but organ donation does give the death meaning,” says Marie-Pier.

On the days when Maxime is overwhelmed with sadness, he clings to words Marie-Pier shared with him: “Instead of five families mourning the loss of their child, it’s only ours. That’s why organ donation is worth it.”

School awareness campaigns are one way to increase the number of pediatric transplants, says Raboisson. The hope is that young people then discuss it at home with their parents.

For Dr. Pierre Marsolais, intensive care physician at Sacré-Coeur hospital in Montreal, identifying those potential donors is key. He looks to Spain, a world leader in organ donation since 1992, when it created an agency to oversee the teams that retrieve organs and support families across all Spanish hospitals. In three decades, the nation more than doubled its donor rate, and the family refusal rate dropped to 14 percent.

Young organ donors have often died accidentally, leaving their parents unprepared, at the worst moment in their lives, to make a decision about donation. In September 2021, an impaired driver violently rear-ended a car stopped at a red light in Quebec City, instantly killing a grandfather and a mother. Her two children—half-siblings Emma, 10, and Jackson, 14—were transported to a trauma centre where they were both declared brain dead. Without thinking twice, Emma’s father, Jean-Dominic Lemieux, agreed to donate his daughter’s organs—five in all.

“Before she passed, I recorded her heartbeat with my cellphone and said, ‘Goodbye, my love. Go save lives!’” he says. Jackson’s father, Daniel Fortin, also donated his son’s organs. He doesn’t feel the need to know who received them, he says. “Maybe one day I’ll want to know more about them, but not right now.” Others do, though.

In fall 2018, two years after their daughter’s suicide, Danielle Lafrance and Michel Carpentier were surprised to get a letter relayed to them by Transplant Québec (as required to protect the organ recipient’s identity). It was from the family of the little girl who received Emmanuelle’s heart. It read: “We are thinking of you. You held out your hand and led us out of our hell.”

That’s how Danielle and Michel learned that their daughter’s heart was beating in the chest of a little girl born with a heart defect who’d undergone two surgeries.

Later, to their astonishment, they realized that the details matched those shared on the Facebook page created for Élissa Grondin, which they’d been following since seeing her story on the news. “We didn’t think it could be Élissa’s heart, because she was five years old,” says Danielle. Emmanuelle was 23 but slight: four feet eight inches and around 100 pounds. Her parents dug deeper and discovered it was indeed possible. “In some cases, the donor may be up to four times heavier than the recipient,” says Raboisson.

A few weeks later, when Danielle was on a retreat in the Gatineau region, she found out that the woman leading her retreat was the aunt of Josée Scantland, Élissa’s mother. Danielle shared her story with the woman, who then promised to pass Danielle’s telephone number on to her niece.

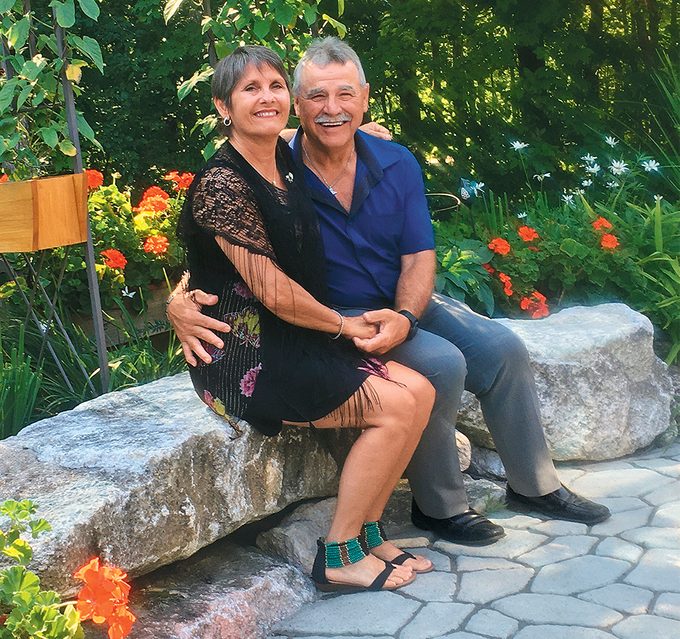

“We were stunned to hear that the donor was 23 years old,” says Josée. In May 2019, the two sets of parents met for the first time in a restaurant not far from Sherbrooke. “We were a little bit apprehensive and a little bit curious,” says Patrick. “Mainly because we didn’t know why they wanted to get to know us.”

“My only concern was that telling them Emmanuelle had committed suicide could hurt them,” says Danielle.

The families got together again in August 2019, this time with Élissa. Josée brought a stethoscope so Emmanuelle’s parents could hear their daughter’s heart in her child’s chest. “It feels like part of Emmanuelle is still alive,” says Danielle with tears in her eyes. Of course, Emmanuelle will live on, in a way, in Élissa, now a healthy 11-year-old.

Élissa keeps a photo of Emmanuelle, given to her by the young woman’s parents, tucked away in her wardrobe. From time to time, she glances at it—so she never forgets the person who saved her.

Next, check out 50 good news stories that’ll restore your faith in humanity.