Growing Up in Northwestern Ontario, All I Wanted Was a Pet Raven

Some ideas are much better in theory than in practice!

As kids growing up in Sapawe, a sawmill town of 200 people in northwestern Ontario, my brother Randy (or Rand as I called him) and I were constantly roaming the forests and gravel roads around town in search of new outdoor adventures. The following is one such story from our childhood.

On the Hunt

One spring, when I was ten and Rand, 11, we decided that our lives would be greatly enriched if we could keep a young raven as a pet. We hatched this idea after we read a book we’d borrowed from the bookmobile extolling the intelligence of the crow family. A raven, a member of the crow family, would certainly be a superior pet indeed. A young bird made the best pet, the book said.

This being late April, a time when young ravens were almost fully fledged, it would be the perfect time of year to capture our unwitting pet. And we knew just where to find a nest full of ravens. A few miles north of town on a logging road appropriately named the North Road, there was an abandoned open- pit mine. The mine itself was a giant gaping hole that had been blasted into the top of a ridge. It was on the vertical rock face of this pit that a pair of ravens nested each year. The time of year was right, the raven nest had been located, now all we would have to do was find a way to coax a young raven out if its inaccessible nest and into our waiting arms.

When the weekend came, Rand and I jumped on our bikes and headed for the mine. We never thought to bring any equipment with us, save for our optimistic young minds which seemed to be all the tools we’d need. An hour later, we reached the spot where the open-pit mine was located. The mine was just a bit off of the road, so we ditched our bikes and picked our way over the snow hummocks, remnants of a slowly retreating winter.

The rim of the open-pit mine was located on the ridge above us and since that was the best place to view the raven nest, we had a bit of climbing to do. Up the slope of the ridge we scrambled, pulling ourselves along by grabbing skinny trees and clambering on all fours. As we crested the ridge top, we stood and stared into the huge gaping hole. Across the abyss was the raven’s nest, situated about halfway down the vertical rock face. As we’d hoped, the nest was full of large fledgling ravens.

So, this was our plan: We would toss stones across the pit which would clatter noisily off of the rock wall where the raven nest was located, and the noise would frighten one of the young ravens enough that it would take its first flight from the nest to the floor of the pit.

As the adult ravens circled above us, croaking their displeasure, my brother and I searched the frozen ridge top for rocks big enough to throw. Fifty thrown rocks later, our plan worked. A young raven jumped out of the nest and laboriously flapped the length of the open-pit mine, making a controlled descent the whole way. We cheered as we watched the bird land on the floor of the crater below.

Scrambling and rolling down the slope of the ridge, we headed for the large opening that was the road-level entryway into the pit. We had never walked on the mine floor before, so we crept forward carefully through scrubby trees and large boulders, our eyes searching for the young raven. The raven was a bit nervous at our approach but soon Rand had his coat wrapped around the bird’s body, effectively subduing its flapping wings. We left the bird’s head and tail uncovered and headed for the mine’s exit.

Second Thoughts

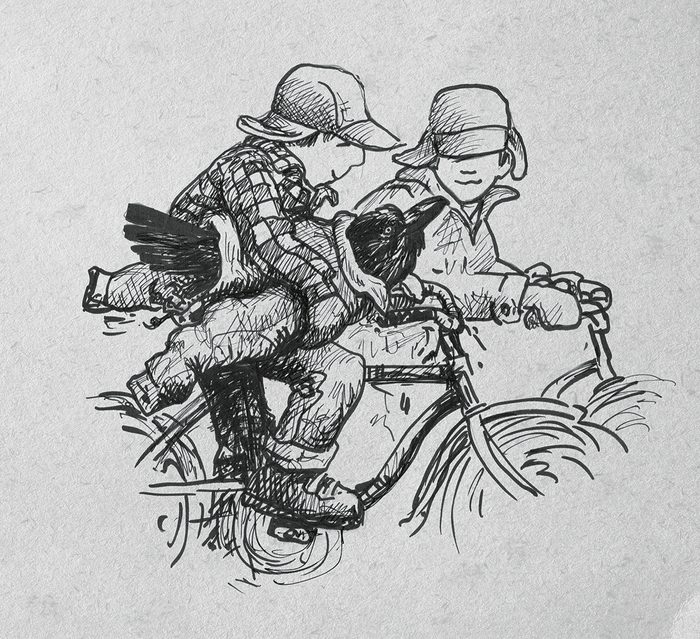

Back on the road, Rand handed the huge wrapped bird to me while he climbed onto his bike. I then handed the bird back to him, which he tried to tuck under one arm while holding the handlebar with his other hand. Brimming with our success, we began to pedal back home.

Our elation was short-lived. We’d only gone a short distance, Rand wobbling slowly along on his bicycle with the raven under one arm, when almost in unison we reached the same conclusion. Without the haranguing of a parent and with only our internal sense of self-governance as a guide, we realized that a bird of this size was not going to be a suitable pet.

So back over the snowy hummocks we went, the raven still wrapped in Rand’s coat. We re-entered the mine pit, unwrapped the bird and placed it as high in a young spruce tree as we could reach. Though it was now out of the nest, we felt confident that its parent would continue to minister to the young bird’s needs in this new location.

We never mentioned our raven quest at the open-pit mine to our parents, but thinking back on this and some other adventures that my brother and I had, I asked my mother later in life if she ever worried about what we were up to when we were off on our outings. Her reply was that with two younger children at home to attend to, it was impossible for her to give all her attention to us. But it was what she added to that sentence that surprised me: “I thought that if the two of you were off together and something happened, at least one of you would make it back home to let us know.”

In conclusion, considering the dangers we courted on that outing, I should finish with this sage advice: “Don’t try this at home.” More to the point, I would suggest that you not make an open-pit mine your playground!

Next, find out what it was like growing up in an Eaton’s catalogue mail-order house.