Learn How to Stop Procrastinating—at Any Age

Procrastination can take a toll on our self-confidence, health and happiness. Here's how to stop it in its tracks.

Trace MacKay puts the “pro” in procrastination. As a pre-teen, she entered a speaking competition and only started writing her speech the night before. In veterinary school, she pulled all-nighters to cram for exams. Now 48 years old and living outside of Sauble Beach, Ontario, she works part-time as a vet and part-time as a consultant. But she still procrastinates on everything from her taxes to work projects.

“I’ll do just about anything to procrastinate. I’ll play sudoku on my phone. I’ll strike up a conversation with somebody,” says MacKay. “Especially right now, working from home, I’ll do some laundry, or go in the garden to water or weed, or take longer reading the paper in the morning than I should—all just to delay starting my workday.”

MacKay has developed strategies to stop procrastinating. She sets early deadlines at work and asks her accountant to book her a personal cutoff a month before taxes are due. But because her procrastination has never gotten her into hot water, MacKay says she’s never been forced to address it. So she keeps delaying.

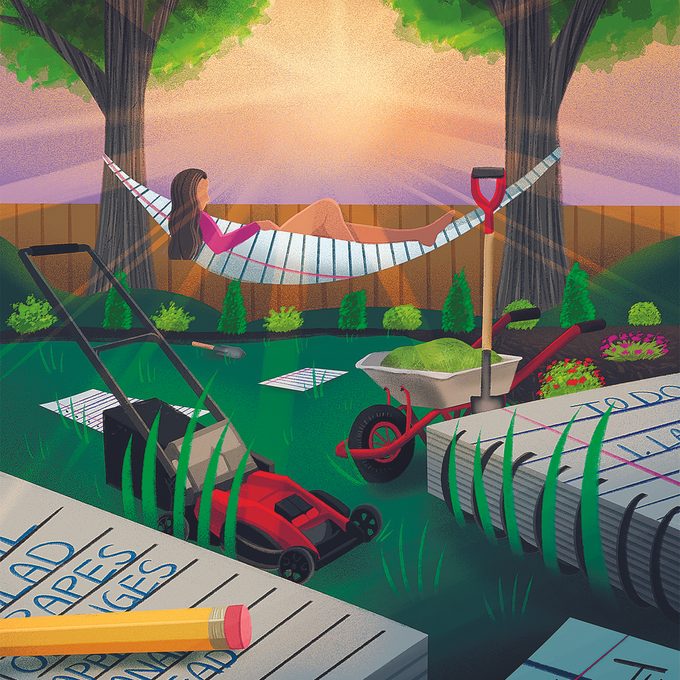

Even if you’re not a serial procrastinator, chances are there are many times you’ve put off a must-do task in favour of doing another, more fun one. In its more harmless forms, procrastinating can lead us to let our yards get messier than we’d like, or delay a much-needed vacation. In its more pernicious forms, it can keep us from having important conversations with loved ones or delay addressing health issues. And it can take its toll on our self-confidence, health and happiness.

Luckily, there are easy and practical steps we can take to stop procrastinating and start living the lives we want to.

How to Stop Procrastinating

The biggest misconception we have about procrastination is that it’s a time management problem. If we make more lists or get a time management app, the thinking goes, we’ll solve all our problems. But such methods rarely work. That’s because procrastination is all about emotional regulation: we procrastinate because we’re hard-wired to choose feeling good in the moment over feeling good in the long term.

“Procrastination is as old as the human condition,” says Tim Pychyl, head of the Procrastination Research Group at Carleton University. “Wanting to feel good now is basically a human need.” Unfortunately, delaying the necessary often creates feelings of regret and shame. The more we procrastinate, the more this cycle becomes entrenched and the worse we actually feel.

Pychyl suggests taking three steps to get your procrastination habits under control. First, learn how to tell the difference between procrastination and purposeful delay. Whereas procrastination is often irrational (you put off filing your taxes even though it will make you more stressed), purposeful delay tends to be rational (you complete an assignment the night before because the pressure helps you perform). Second, realize that when you’re procrastinating, you’re acting against your own self-interest. And lastly, learn to forgive yourself for messing up.

Identify the First Step

The next time you’re tempted to procrastinate, Pychyl says to ask yourself: “What’s the next action I would take on this task if I were to get started on it now?” Have an important project at work you’re not sure how to get started on? Set a meeting with your boss to clarify expectations. Want to finally tackle that home renovation project? Make a list of the tools and materials you’ll need to do the job. Setting a manageable and realistic first step shifts your attention from feelings of uncertainty or fear onto a low-stress, easily achievable action, and it also gives you a sense of agency. “Our research and lived experience show very clearly that once we get started, we’re typically able to keep going,” says Pychyl. “Getting started is everything.”

Dr. Piers Steel is a professor of organizational dynamics and human resources at the University of Calgary who began studying procrastination because of his own struggles with it. “These are not exactly difficult lessons to learn,” he says. “But we never got cc’d on the instruction manual for our own brains.” Steel suggests that framing actions in terms of time can also be helpful: what can you do in the next 10 minutes, or before lunch?

For example, say you want to Marie Kondo your basement, but the thought of tackling your piles of stuff makes you want to slam the door shut and run in the other direction. Instead, try dividing your basement into sections that can be tackled in 30-minute increments. Set a goal to do one per day, and get started on the first one immediately.

Use Your Power Hours

Give yourself an even better chance of succeeding by setting cues and intentions for yourself, and learning how to maximize your power hours.

Setting cues and intentions is all about making it as easy as possible to follow through on a task or goal. Say you’re struggling to establish an exercise routine in the mornings. Try setting your gym clothes out the night before and putting your shoes by the door. Keep forgetting or putting off doing breast self-exams? Set an intention to do one every time you’re in the shower.

Making the most of your power hours, meanwhile, is all about scheduling tasks for the time (or times) of day when you’re at your most productive and motivated. Want to train for a 10K run? Assess when you have the most energy to exercise. Need to pull together a family savings plan? Figure out when you and your partner have the most brain space for what could be a stressful conversation.

This approach has worked for MacKay, whose most productive hours tend to be right before lunch. Conversely, she’s learned not to bank on her afternoons: “That’s prime napping time,” she says, laughing. “I know then I’ll think, ‘Oh, I have so much to do. I should probably go have a nap.’”

Pychyl stresses that conquering your procrastination isn’t just about feeling better in the moment—it’s about having more agency over your life. “Time is a non-renewable resource,” he says. “We just don’t know how much we’re going to get of it. We need to stop playing around at the edges and get on with it.”

Ready to stop procrastinating? Start with these tips on how to live a happier life!