Inside the Long Battle to Save B.C.’s Old-Growth Forests

More than 30 years ago, diverse groups joined to protect B.C.’s old-growth forests. What lessons do they have for today’s environmentalists?

The cabin where it all started

Tla-o-qui-aht Elder Joe Martin slows his motorboat around an eastern fin of Meares Island into Cis-a-qis Bay. It’s taken 30 minutes to get here from Tofino, a popular surf town and tourist hub on the west coast of Vancouver Island in Clayoquot Sound, B.C. “Can you see it? Can you see the cabin?” Martin’s friend Leigh Hilbert asks, pointing out a silver speck in the distance.

Also on the boat are Joe’s daughter Gisele Maria Martin, an educator and Tribal Park guardian, responsible for the environmental, archaeology and stewardship monitoring of Meares Island, and us non-Indigenous guests: myself, Hilbert and Hilbert’s partner Oona. We coast on the glassy inlet, anticipation swelling with the rising tide. Then, I can see the hand-built wooden dwelling beneath a curtain of cedar boughs. Nailed to the siding is a small green stop sign with the words “Log for the Future—Stop Clearcuts.”

“Welcome home,” Hilbert says to himself.

The 1993 Clayoquot Sound blockade, known as the War in the Woods, gained international attention and set off a chain reaction of efforts to protect B.C.’s old-growth rainforests. But a decade before, a quieter resistance took root here on Wah-Nah-Jus Hilth-hoo-is (Meares Island). It’s not as well known as the Kennedy Lake Peace Camp, where nearly 900 people were arrested. And neither it nor the War in the Woods ended the clearcutting of old-growth forest. But the campaign to protect Meares Island is an inspiring early example of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people working together to defend the land.

It’s been 20 years since Hilbert has seen the 320-square-foot cabin that served as the de facto headquarters of Canada’s first logging blockade. That cabin is also where Martin and Hilbert cemented their bond. Over nearly five decades of friendship, nothing compares to the winter they helped save Meares Island from chainsaws.

Martin leads us inside the cabin, as he and Hilbert walk across the creaky floors and reminisce. A cupboard door broken off at the hinge is carved with a moon symbol. Gisele explains that sun and moon crests often represent iisaak, an important Indigenous law that is also a verb, meaning “to observe, appreciate and act accordingly.”

Martin, now 67 years old, and Hilbert, now 70, stop at a display of sepia photos, warped by time and water. Memories flood back. Of Martin’s late father, Tla-o-qui-aht hereditary Chief Robert Martin, who lived at Cis-a-qis for three months with his partner during the winter of 1984–1985. Of Hilbert doing media briefings via two-way radio. He shows us the wood stove that warmed those who joined the forest protection effort, sometimes 30 in this small space.

“There were sleeping bags side by side by side,” Hilbert says. “We were here for the entire winter. We were determined.” Gisele, who was only seven during the encampment, remembers lots of singing. “What in the world can we do? I’ll hug a tree, won’t you?” she starts performing, reciting the chorus to one of the tunes from “Songs for Meares Island,” which was eventually recorded and sold as a cassette tape to raise funds for the blockade. “There were people from all over who came here,” Gisele says. “That strength and unity was really warm.” And, as today’s movement to defend old-growth forests gains ground once again, there are many lessons to be learned from past efforts to preserve the forests and watersheds of Clayoquot Sound.

Saving Meares Island

Hilbert and Martin met in the mid-1970s working for MacMillan Bloedel, a multinational timber company that was once the largest private corporation in B.C. Hilbert moved from Seattle to Tofino in 1973 to take an engineering job designing logging roads and cutblocks, areas where forest is razed for timber, around Clayoquot Sound. While Martin rigged machinery to drag logs, Hilbert was usually surveying ahead of the road-building crew. He remembers, in the early days, passing one mammoth tree after the next as they penetrated deeper into the forest, ancient cedars and firs dropping behind him like bombs.

Hilbert knew how rare temperate rainforests were—the misty, carbon-rich coastal landscapes covered less than 1 per cent of the planet to begin with. Not only was it the age, but the sheer size of the trees floored him. He recalls coming across two enormous western red cedar trees near Whitepine Cove. When he wrapped his survey tape around the butt of the largest one, the tape read about seven metres in diameter. “I had never seen anything like it,” Hilbert says. “I thought, ‘We can’t be cutting this down.’”

That conviction led Hilbert to quit his job exactly a year after starting. But having had access to the company’s projected logging blueprints, he began alerting people like Martin about the forests’ planned future. In 1979, this knowledge helped spark the formation of the environmental group Friends of Clayoquot Sound. On the proposed chopping block: Meares Island, an 8,500-hectare land mass that was home to some of the province’s largest red cedars and about 350 Tla-o-qui-aht residents.

By 1981, opposition from Friends of Clayoquot Sound, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and their allies prompted the government to set up the 11-member Meares Island Planning Team. The Ministry of Forests tasked the group with creating an “integrated resource plan” that acknowledged the island’s non-timber values, such as Indigenous culture and recreation. But after more than three years and three proposals, the B.C. government instead accepted a counterproposal from MacMillan Bloedel and B.C. Forest Products to log 53 per cent of the island over 35 years.

And so a new idea sprouted: an encampment at Cis-a-qis (Heelboom) Bay. It was here that the Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousaht First Nations declared Meares Island an Indigenous protected area, or Tribal Park, in April 1984. According to MacMillan Bloedel’s blueprints, the bay would be the start of a new logging road into the heart of the island’s old growth. So Hilbert built a cedar-shake cabin, nestled between two living cedars, to monitor the entrance.

The thought of large-scale destruction on Meares Island— slated for $25 million worth of logging—galvanized a diverse cross-section of society to join the protection effort. Tofino doctors, lawyers, business owners and town councillors joined forces with First Nations leaders and nature-loving drifters. Money and legal aid started flowing in. So did supporters from Haida Gwaii and California, and media from all over the country. Nothing went ahead without the blessing of Tla-o-qui-aht hereditary Chiefs and Elders, as well as the elected Chief at the time, Moses Martin, Joe Martin’s uncle.

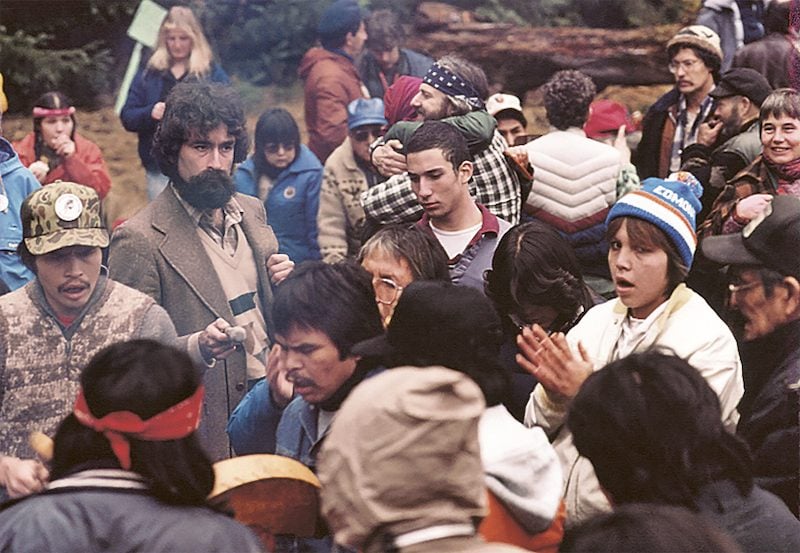

Moses, who’s now 79, played the central role in a historic standoff on November 21, 1984. Around 250 people were on the beach and in the water trying to block MacMillan Bloedel’s 40-foot crew boat from sailing in. When nine forest managers and three fallers armed with chainsaws arrived at the island declaring their right to the tree-farm license, Moses read his own declaration of Tla-o-qui-aht rights and title. Then, with a sweep of his arm, he invited the workers into the Tribal Park for a meal, but only if they left their chainsaws on the boat. The crew remained on its vessel.

Industry power

Forest defenders successfully warded off MacMillan Bloedel’s road building and tree harvesting all winter long. And on March 27, 1985, they celebrated their victory moment when the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled that no logging could take place on Meares Island until Indigenous land claims had been settled. It was the first court injunction preventing logging in the province’s history. It’s still in effect today. “The forest is still standing,” Martin says. “And I think it inspired people across the country to stand up for their rights.”

Several more logging blockades and court cases followed, leading up to the faceoff at the Kennedy River Bridge near the Ucluelet-Tofino junction in 1993. Nearly 900 people were arrested there, making it one of the largest acts of non-violent civil disobedience in Canadian history. Two years later, the Forest Practices Code became law under the NDP government, bringing in new regulations for cutblock size, road building and buffer zones for salmon habitat. The Forest Practices Board was created as a “watchdog” to ensure proper management of B.C. forests—95 per cent of which are on public land.

Some of those victories were more short-lived. An industry-led crusade to weaken regulations, followed by the shift to a Liberal government in 2001, significantly eroded the Forest Practices Code, which was soon replaced by the Forest and Range Practices Act. Oversight was outsourced to “qualified professionals” working for timber companies, effectively privatizing public forests. From 2004 on, conservation could only happen “without unduly reducing the supply of timber.”

In the name of global competition and better U.S. relations, the provincial Liberal Party leader at the time, Gordon Campbell, also scrapped two measures that supported local economies: a condition requiring companies to process logs in the region they were harvested and a program that would have provided funds to build a value-added timber industry. All of this opened the door to raw-log exports, the shipping of unprocessed logs to the highest bidder overseas, which doubled on the coast between 2000 and 2016. During the same period, 44 mills shut down and 32,000 forestry jobs were lost.

Today, a quarter of the annual harvest, or half of everything logged on Vancouver Island and the coast, is old growth. Red cedar—the most valuable tree species in a lumber market that’s been booming due to pandemic-inspired U.S. home renovations—is of particular importance to the logging industry. In September, it was selling for US$1,600 for a thousand board feet, which is almost double the price of spruce, pine and fir.

A study released last April found that of the 13.2 million hectares of remaining old growth in B.C., less than three per cent still contains the monumental trees that most people picture when they think of old-growth forests. Productive old forests are “effectively the white rhino,” the study states. “They are almost extinguished.”

Lessons for today

Growing awareness about how little old-growth forest is left has ignited a new push for protection. In 2016, the Union of B.C. Municipalities—representing more than 150 city, town and regional governments—passed a resolution calling for an end to old-growth logging on Vancouver Island. In 2018, more than 220 international scientists signed a letter urging the province to conserve its globally rare temperate rainforests for the sake of the planet. Several First Nations have rolled out conservation strategies focused on the old-growth red and yellow cedar trees so integral to their cultures.

On September 11, 2020, the NDP government released a much-anticipated review of old-growth forests in B.C. The independent report, titled “A New Future for Old Forests,” calls for a “paradigm shift” that prioritizes ecosystem health over the timber supply. Following the passage of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act in late 2019, the report lists Indigenous involvement as recommendation number one.

Coinciding with the release, former Forests Minister Doug Donaldson announced the deferral of old-growth logging within more than 350,000 hectares, as well as the protection of up to 1,500 giant trees. The total area of old growth in the protected space comprises about 1.5 per cent of B.C.’s mature forest and is roughly the same amount that’s currently harvested every year.

Many conservationists believe the move didn’t go far enough. They argue that Clayoquot Sound, which makes up nearly three quarters of the moratorium, was already less vulnerable because of Forest Stewardship Council certification and decades of resistance. The government’s announcement also didn’t cover the province’s most at-risk forests.

Despite these shortcomings, others are celebrating the news for Clayoquot Sound. Clayoquot—an anglicized version of Tla-o-qui-aht, which contains a root word meaning “moving and changing behaviours and emotions”— is a place where Indigenous leaders and allies have stood up time and again to protect their lands and waters, and the creatures and humans that rely on them. It’s a place where humans are a keystone species in those lands and waters. It’s home to cultures that teach the law of iisaak. Observe. Appreciate. Act accordingly.

Back on Meares Island, sunlight streams through cedar and hemlock branches, casting a tangle of berry bushes in a moss-green glow. Joe and Gisele stand outside the cabin where a group of individuals lived for a winter to protect the island’s forests. As the Martins pick huckleberries and talk about their ancestral connections to cedar and salmon, I get the sense that they’d do it all again.

Here’s what it’s like to photograph grizzlies in British Columbia’s Great Bear Rainforest.

© 2020, Serena Renner. From “The Deep Roots of BC’s Old Growth Defenders,” The Tyee (September 16, 2020), thetyee.ca