This Spring May Be My Last, So I’ve Decided to Stop and Steal the Roses

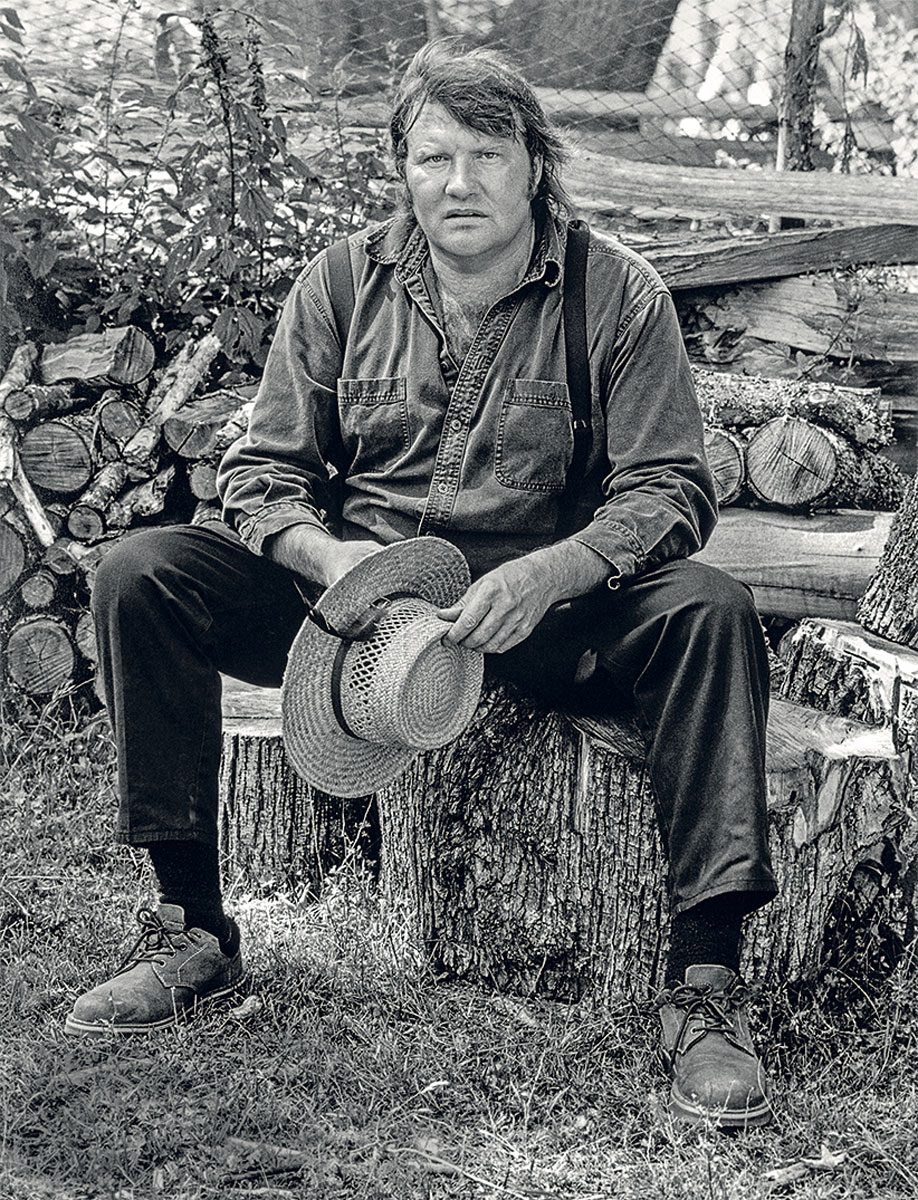

Given only months to live, Vancouver writer and poet Brian Brett surrounded himself with stolen beauty.

The Flower Thief

I am the flower thief of Vancouver. I’ve been a predator of beauty all my life, and beauty has had many faces.

As a child of the ’50s, beauty was a plum tree glistening purple, with dripping sap, cracked plums and ecstatic yellow jackets circling my semi-naked monkey body as I clambered through the branches, somehow unstung, filling my T-shirt with the sweet, sticky crop from the tree.

At first, my predations were mostly gardens, though I did branch out into comic books and chocolate bars until my ruthless, righteous mother caught me. Oh the shame of being marched down to the local convenience store and abjectly apologizing while I paid everything back.

My crooked ways soon returned. I was an incorrigible child. We discovered the old lady’s carrot patch down the street. We would crouch in her garden and yank the tender young carrots out, rub them clean and munch them down like Bugs Bunny before running, shrieking for our lives when the cane-wielding old lady appeared.

This was followed by the discovery of the watermelon farm. How I miss those seedy, ineffably sweet watermelons, along with the cow corn we ate raw, also sweet, only starchy. I miss smashing the stolen melon with my bare fist, scooping out the red flesh. I miss the seed-spitting contests in the shade by the creek. Then, in the summer heat, leaping into the rushing, clean water, clothes and all. Today, both creek and field are potentially toxic, while the new hybrid watermelons have lost their teeth-hurting intensity.

One day, we kids were raiding the ancient man’s garden across the street. He grew the best raspberries. Suddenly, the man came hobbling out the door wielding a broom and I scurried home. He followed me to my door—and then inside! My parents were at work. I was terrified, so I slithered under their bed as he stalked through the rooms, grumbling and waving his broom. He shoved it under the bed where I was hiding, just missing me. Fortunately, he couldn’t manage to lean down far enough to see me. He left the house, slamming the door, cursing his way home.

My nefarious instincts returned again when I was a student at Simon Fraser University. A lovely woman had joined me at my home in White Rock and, while walking the beach road, I noticed a row of enormous sunflowers growing alongside a shed.

That night I returned with a knife, hacked off the largest head and kept it in a jug on the kitchen table. The sunflower impressed the lady, though a few days later the guilt crept in and has stuck with me ever since, almost 50 years. The more I took to my own gardening, the more I regarded myself as a crud, especially since I’ve never been able to grow a sunflower as large as that regal, stolen giant.

By 1980, I had become almost too obsessed with gardening. Cultivating a garden made me a fierce protector of my plants, along with those of my neighbours and public gardens, too.

Then came the brutal July of 2015. I lost my health to one of those ferocious hospital bacterias. I also lost the love of my life, who changed her mind about me after 38 years. We had to give up our farm paradise on Salt Spring Island, with its orchard and large garden that I’d dream-fantasied into existence when I was 17 years old.

In February 2019, once again a lowly renter in Vancouver, my new surgeon told me I was too far gone to operate on a newly diagnosed liver cancer. I had less than a 50 per cent chance of surviving the year. Not that I believed him, but the thought of being shut down so suddenly made me consider the possibility that it was my last spring.

I walked out of that doctor’s office, angry at his rude dismissal, then recognized how blue the sky was. It hadn’t been that blue since I was 12 years old, when I scratched “There are 287 kinds of blue” on the back of my clothes dresser, along with the name of a pretty young girl I knew in Grade 6, so that neither would be forgotten. And they weren’t, though the dresser is long gone.

What a weird spring we had in 2019, such a crazy unleashing of blossoms. I realized I had to pay attention to every one of them. Then my heart specialist decided to compete with my oncologist for the role of Doctor Doom. She told me that my chances for another spring were even slimmer.

My last flowers! The deranged flower prowler was unleashed. At first I nabbed them mostly with permission from people’s yards, or off the boulevards. My bedroom became thick with magnolias, camellias, quince and crabapple. My brightest spring ever.

I still believed I was unkillable, though I suspect everyone thinks that when they receive the death penalty. I continued on my raids. I know that snatching flowers is a cruel thing to do, but I also knew what I was doing, so the pruning was very artful.

Also, in a further plea for leniency, I generally stuck to the public boulevards. While the city has some brilliant arborists, it clearly doesn’t have enough staff to properly prune everything, so I tidied up the trees as I snatched the blossoms. You may call this vigilante pruning or, more artistically, guerrilla ikebana.

This is not something the average idiot with a hacksaw should practise. Pruning is a complex business. For instance, I sterilized my pruning shears in between trees so I didn’t pass any disease from one tree to another.

As I carried out my forays, I thought of a quote attributed to Buddha: “Attention leads to immortality. Carelessness leads to death. Those who pay attention will not die, while the careless are as good as dead already.”

I thought, too, of what the good Dr. Johnson said: “When a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”

That’s why I became enamoured of the two splendid camellias that grow in my yard. Many centuries back, an intrepid Japanese gardener noticed that certain camellias faded, even as they bloomed. Rather than breed them to correct that flaw, he bred to enhance it so that his fellow citizens would understand the transience of life and death’s presence, even in these elegant, near-perfect blossoms.

It never occurred to me that so many flowers would soon clutter the house. Since there were already orchids at my bedside, the room had grown crowded very quickly. (I kept the orchids so that if I should die in my sleep, they will be the last things I see when I extinguish the lights.) This beautiful dilemma was worsened by my kitten, who discovered that vases full of quince, cherry, plum, camellia, roses and peonies made for excellent batting practice.

And yet, I went out for more. If a particularly spectacular flower was in a yard, I would ask someone at the door for a cutting. Even those who don’t speak English figured me out quickly, with my pruning shears and my pantomimes pointing at a branch. They invariably nodded yes.

Only one person turned me down. I trudged up to a door and knocked, and could see through the curtains a large man and a woman snuggled up on the sofa, watching TV. They never moved. So I knocked again. She rose and walked to the window by the door, pulled the curtain aside, stared at me and then returned to the sofa.

This so inflamed me that I chopped off a dangling branch of her beautiful magnolia as I returned down the sidewalk. Now I feel guilty about that one. She might have been harassed by a local gang or was a frightened refugee; there could have been any reason for her rudeness.

I took early evening walks to map out the best flowers. When the light faded, I dashed in and had at them like Edward Scissorhands, turning some bedraggled hawthorn or Magnolia liliiflora Nigra into a beauty before fleeing with my ill-gotten gains.

I should receive a good citizenship award for donating my decades of pruning skills to the city for free, but I’ll probably get arrested for writing this article.

Vancouver is noted worldwide for its exquisite public trees. Some of them have a complex history. For example, Vancouver’s original 500 sakura, or cherry trees, were a gift from the mayors of Kobe and Yokohama, who wanted to express their gratitude to the Japanese-Canadians who served in the First World War. Unfortunately, we repaid them 10 years later by interning all Japanese residents in prison camps.

Now there are around 20,000 cherry trees in multiple varieties planted among magnolias and plum and hundreds of other trees.

Looking up the history of my local trees made reality return with a vengeance, and I realized with some horror what I had been doing, so I set down my pruning shears again. “O mother tell your children not to do what I have done!”

Treat our city of gardens with respect. Save the flowers for your children. Yes, pay attention!

Me? I was rewarded with a new diagnosis of survival for an extra year.

Though another spring is here, no longer will I prowl our evenings, pruning shears in hand, even though my damaged heart is exploding like a deep red rose.

Stolen beauty has a special, dangerous quality. It’s also a destructive quality, never as special as natural beauty admired in its natural place. Our real duty is to bloom and grow bright, then fade and die.

Next, read the inspiring story of Verna Marzo—given only a sliver of a chance at survival, she is now an amputee marathoner.