“I Am Reclaiming What Culturally Belongs to Me”

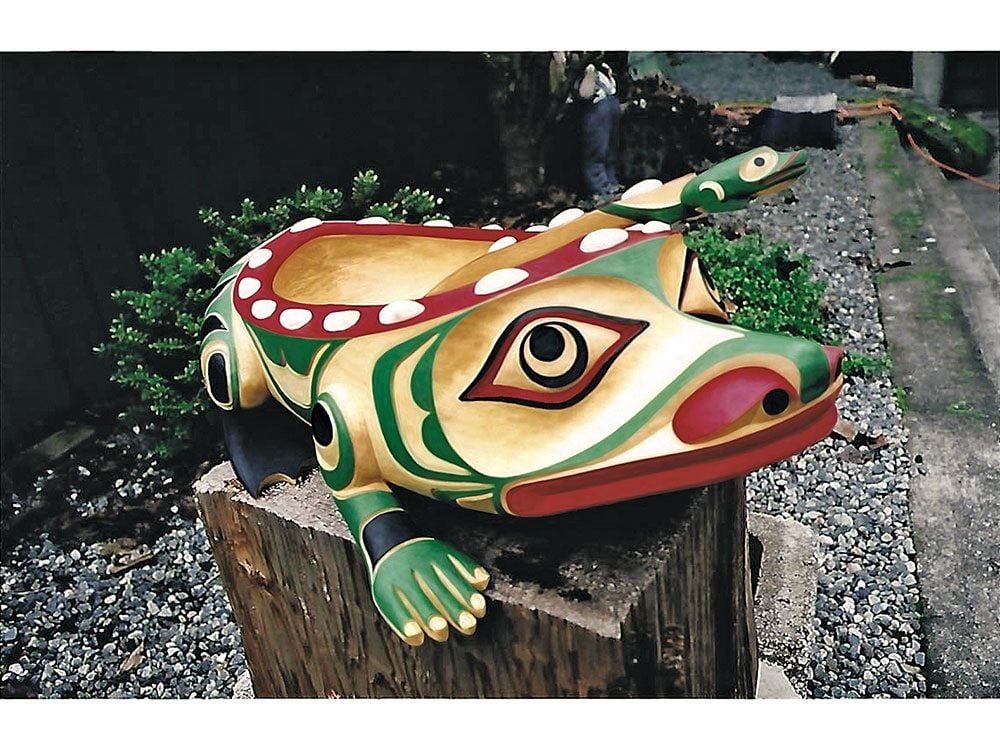

Firstly, I would like to say that I don’t call what I do art. I refer to it as cultural property, meaning it comes from my culture and I own it. Each time I carve a piece of artwork, I ask myself if it would be accepted in the Big House, where gatherings are held and decisions are made. If not, there is no point in me carving it. Every piece of work I do, I feel I am reclaiming what culturally belongs to me. When I make something, I am claiming the rights to it for myself, and at the same time for our children and all Kwakwaka’ wakw people. They are the ones who really own it.

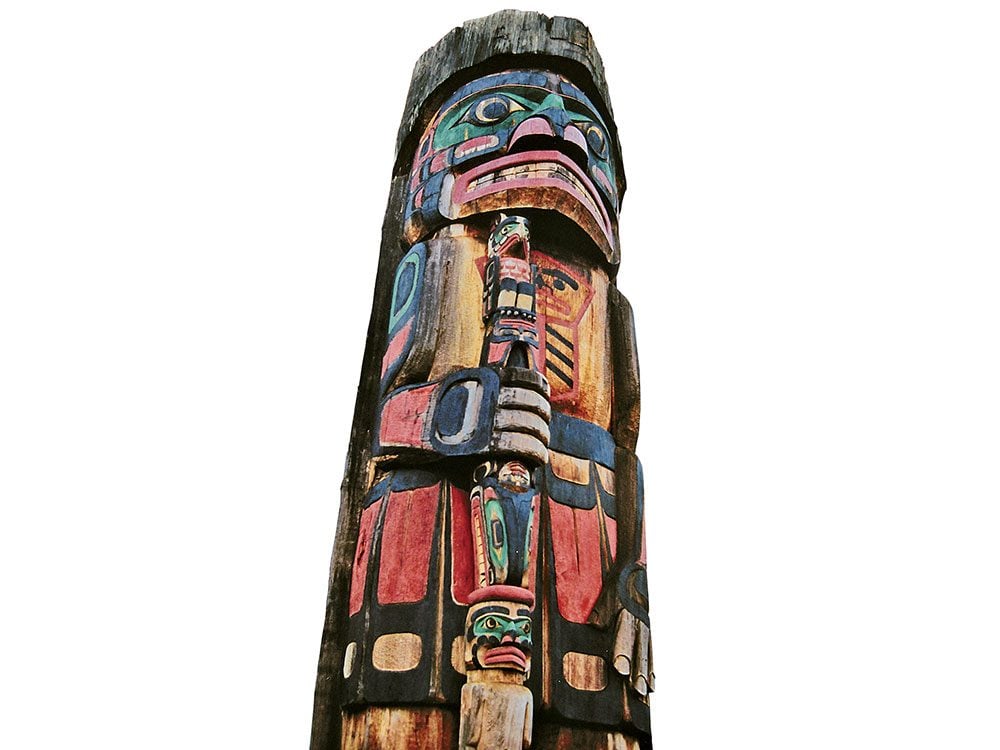

Our ancestors paved the way for us. I try to remember to thank them for keeping our traditions and culture alive. They went through a lot of hardship for us. The main influence in my artwork came from my father, Henry Hunt, as well as from Willie Seaweed’s work. These are the people who turned our works from being considered a craft to being regarded as historical art. I also love the Mayan and Egyptian cultures because several of our beliefs are the same.

Meet the woman working with First Nations elders to preserve Canada’s plants!

“I Do Not Condone Non-Natives Doing Native Art”

I believe the time has come to recognize our works as cultural property. Culture is one of the last things our people have, and I think the time has come for our chiefs to stop giving it away in the Big House.

I do not condone non-Natives doing Native art. My work comes from my culture; it belongs to all Kwakwaka’wakw people and me. We have legends and traditions around each mask and each dance we do, and we take our culture seriously.

I was fortunate to make my living as an artist, but it was not always easy. I try to counsel young artists to first get their education. I tell them to get a good-paying job and have their art as their hobby until they become established. It is sad to see artists struggling who don’t have anything to fall back on.

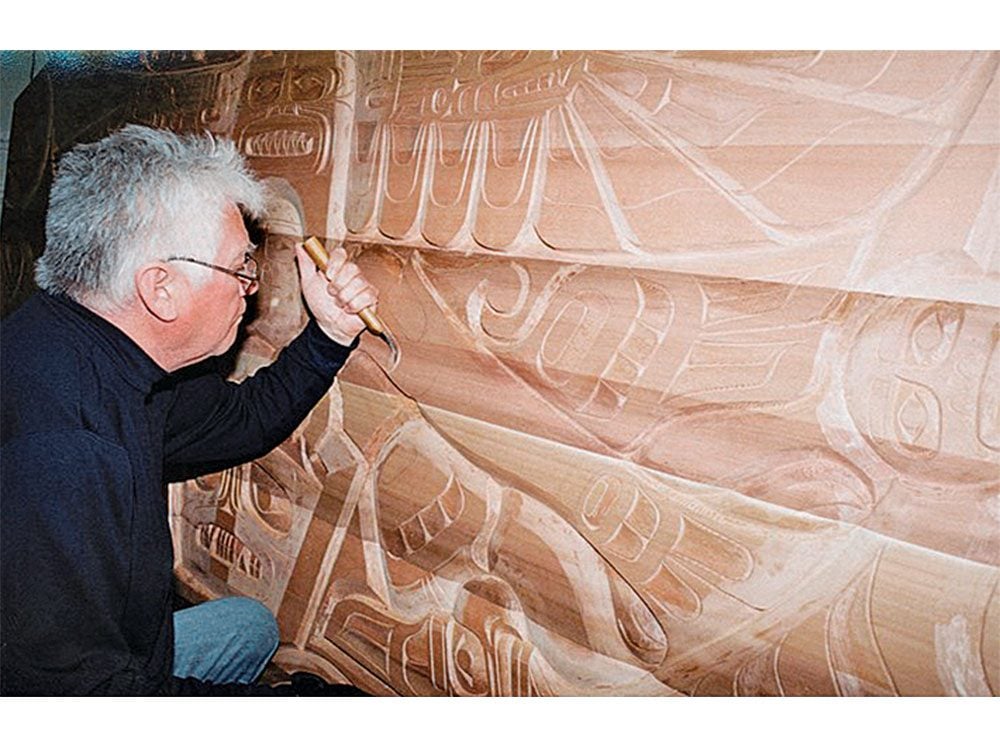

When I was 13, I decided that I wanted to be a carver. My brothers and I had gone berry picking in Saanich, B.C., to make money. I dreamed of berries all that night, and woke up the next morning knowing that I wanted to be a carver, like my dad. My mother told me to go and learn from my father, and that’s how I started, making little paddles and masks. It was a hobby that turned into a way of making an income through my school years. I was fortunate to have good teachers in high school. They saw my talent and encouraged me with books and time off from class to go to Thunderbird Park to carve with my dad. They wanted me to be successful, and looking back, I may have chosen a different road in life if not for their encouragement.

Plus: An Inside Look at the Work of Sioux Artist Maxine Noel

“I Will Carve Until I Die”

The more I carved, the more I realized that what I was carving came from my culture. That is why I believe that what I create is cultural property and it is my job to educate the public about my culture as much as I can to keep it alive.

Today, I am finishing work on a 15-foot totem pole for a private collector. This may be my last totem pole, as I am 66 years old and my hands are getting sore, but I have always said, like my dad always said, “I will carve until I die” and I don’t plan on going anywhere just yet.

I have been married for 33 years to my wife, Sandra. We have a daughter, Emily, who is 27, and a bichon named George. Life is good.

To find out more about Richard Hunt, his artwork and his community involvement, click here.

Check out How the Watchmen of Haida Gwaii Preserve the Past.