How Traditional Tips Can Help Us Mourn in the Modern Era

There is no easy way to work through loss, but historical advice can help mourners chart a healthy path through grief.

A new mourning

My daughter Hannah was deep in wedding preparations when her fiancé, Scott, was killed in a car crash in January 1998. She was a 25-year-old medical student and not much interested in history, so she knew almost nothing about how people in previous times had mourned. And yet, in the months after Scott’s death, without realizing it, she recreated many traditional mourning customs from around the world.

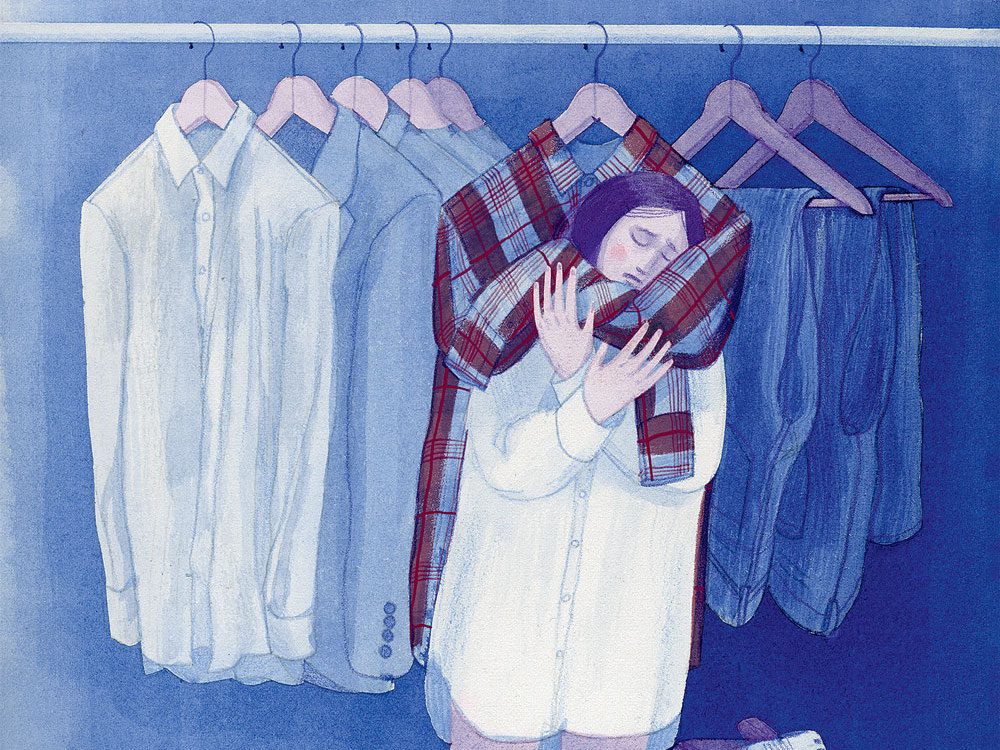

Like Queen Victoria or mourners in ancient Rome, she wore special clothes—something of Scott’s every day. She remembered him in company, taking an unintentional cue from bereaved Jews who say Kaddish, the mourner’s prayer, together in synagogue every day for up to 11 months. “The Scott Coffee” met every Sunday at his favourite Vancouver spot to flip through a photo album of his and Hannah’s, sharing memories. Many cultures have long followed a mourning timeline, the period during which, for example, people donned black or limited their social lives. Hannah also did this, wearing her engagement ring on her left hand until the one-year anniversary of Scott’s proposal. After, she moved it to her right hand.

Our era has worked hard to minimize mourning, a shift that started in the aftermath of the First World War. Following the unthinkable losses of the war—and also, among other reasons, the belief that medical advances would relegate death to a concern only for the very old—many people began to see grieving traditions as old-fashioned, irrelevant and morbid. Very gradually, in the past few decades, the pendulum has begun to swing back as people realize mourning, and death, are too important to be sidelined.

Years later, when I asked Hannah about her wholehearted mourning, she told me about the sadness she experienced when her father and I divorced. She was nine when it happened, but she never cried about it and never wanted to talk about it. With Scott’s death, she wanted to let herself experience the fullness of her grief. “I wanted to do the work,” she said, “and have the worst part over.” Hannah found her way on the mourner’s path by instinct, but there are some traditional tips that would benefit many bereaved people.

Mourning requires some effort

Sigmund Freud wrote about “the work of mourning,” a bereaved person’s painful acceptance that their beloved is no longer alive. Freud believed the relationship could evolve into a continuing, internalized bond—one that allows the mourner to achieve a new normal. Such work is enormously flexible and individual and can range from actions like Hannah’s “Scott Coffee” to hours spent staring at a wall, remembering the dead and wishing for their return.

Rosa Spricer, a Toronto psychologist, says, “Research shows that people from cultures that allow them to fully grieve for a long period of time tend to have less complicated and unresolved grief.” But paying attention to your grief can be easier said than done, she adds, especially if your usual way to deal with difficult feelings is to ignore them.

Sarah Kennedy, a registered clinical counsellor in Vancouver, agrees that stifling grief can lead to long-term difficulties. Often, clients who’ve tried to repress their grief arrive in her office with anxiety, sleep problems, relationship difficulties and more. “An array of symptoms can come knocking, as if to say to the denier, ‘You’ve forgotten to take care of something important here,’” she says. While mourning can be frightening, she adds, speaking of her most resistant clients, “They know that grieving is the medicine they need.”

Choose the right support system

Bereavement can be a time of great loneliness, when friends and family are more important than ever. But the modern aversion to discussing death has left many of us inhibited and clumsy in these situations. People may inadvertently downplay the mourner’s plight or say the wrong things, like, “Are you still brooding about that?” or, “Life goes on. It’s time to forget the past.”

Unfortunately, during a fragile time, such false steps can feel like abandonment, says Spricer. These failures in friendship and family are common, she adds, but they don’t have to be. Some mourners benefit from directly stating what support feels best for them. Spricer recalls, for example, a church funeral at which attendees found instructions titled “Ten Things Never to Say to a Mourner” at every seat.

Kennedy’s clients often mention a “failure of attunement” from family and friends. When they experience others’ impatience with the speed of their mourning, she urges them not to internalize a sense of failure. “People need to be discerning about whom they open up to when feeling vulnerable and overwhelmed by their feelings,” says Kennedy. When looking for confidantes, head for good listeners, not those who jump in quickly to tell you what you should be doing.

Hannah also chafed at friends who didn’t respond as she hoped but now suggests trying to cut friends and family some slack. When you feel better, you will likely find their friendship is still worth having.

Remember you’re in charge

People who attend an Orthodox Jewish shiva, or condolence visit, don’t approach a mourner unless the mourner beckons them. The mourner’s instincts and wishes are paramount. That’s something to keep in mind whatever your religion (or lack of religion). “There isn’t one way to grieve,” Spricer says. “Every mourner comes to loss with their own history and their own ways of coping with emotion.”

In other words, mourning isn’t one-size-fits-all. Don’t let anyone tell you what to do, how you should feel, or how long it will be until you feel better. Even when two people are mourning the same loss—siblings, for example, who are mourning a shared parent—each person has to be able to choose their own path. This can be a source of friction or hurt to the other person, but it needs to be respected.

When it came to mourning, Hannah marched to her own drummer. More than 20 years after Scott died, she is a busy doctor, wife and mother, but for a long while she still wore his engagement ring on her right hand. To her, it was the sign of a well-earned, continuing bond that coexisted healthily with her current life.