A COVID-19 Patient’s Incredible 77-Day Fight for Survival

The story of Rick Cameron's battle for survival, the doctor who wouldn’t give up, and the Maritime community that rallied around them both.

Rick Cameron was tired. His body ached, and his breath seemed to catch in his chest—a bout of the flu, he assumed, something he’d picked up from the grandkids who’d been clambering over him the week before.

It was Friday, March 13, and in Stellarton, Nova Scotia, the coronavirus still felt like a distant threat. It was an item on the news, not something that could plausibly find its way to this sleepy maritime town.

At 69 years old, Rick was healthy and strong, a six-foot-two former athlete who had spent decades coaching youth hockey. He’d grown up in a tiny village on the coast and spent 41 years at the Michelin tire plant in Pictou County, working his way up from forklift driver to industrial engineer to business analyst. He’d met his wife, Faye, when he was 17 and she was 15. Rick was blond and outgoing and “pretty hunky,” Faye remembers. On Saturdays, after helping his dad on the lobster boat, he’d pick her up in his prized Ford Falcon and drive to dance night at the local rink. They married four years later. It was a relationship, their daughter Kelly used to complain, that was so impossibly conflict-free that it had ruined her conception of what a marriage should be.

Kelly, a 40-year-old manager at Money Mart, had never really worried about her dad. He’d always been the one to take care of her and her brother Jeff, helping her through her battles with depression as an adult, bringing his insistently positive attitude to the worst situations. After a house fire a few years ago, she and her 44-year-old husband, Brian, had moved into her parents’ three-bedroom Cape Cod–style home in Stellarton. The four of them have lived together ever since.

That weekend, with her dad already self-quarantining in the basement, Kelly stood at the top of the stairs and listened with growing concern as Rick weathered coughing fits that seemed to shake his entire body. On Monday, Rick and Faye drove 40 minutes to the ER in Truro. Masked health-care workers examined him and asked him if he’d been out of the country recently. He told them he’d vacationed in Florida for two weeks in mid-February, but that was nearly a month earlier, well past COVID’s two-week incubation period. The hospital said it was only a viral infection and released Rick, telling him to take some Tylenol and get some rest.

As the week went on, however, Rick got worse. By Wednesday, he was so weak he could barely move. By Thursday morning, he struggled to breathe. “I think you better call an ambulance,” he told Faye. To reduce the possible spread of the virus, family members weren’t allowed in hospitals. As the ambulance was leaving, Faye rushed out to give her husband his phone and say goodbye.

At the hospital in New Glasgow, doctors swabbed him for COVID before transferring him to Truro, where doctors had created a COVID unit in anticipation of a possible epidemic. That evening, doctors called Faye to tell her the news: her husband had tested positive for COVID-19. They weren’t sure where he’d caught it—possibly in the community, possibly from someone else who had returned from the States. “What do I do now?” Faye asked. “Pray,” said the doctor.

That night, so weak he could barely work the phone, Rick called his wife. “Don’t get upset,” he said. If she started crying, he knew he’d start too. The doctors had a plan, he assured her. Before he said goodbye, he apologized for putting her through all this. He told her he loved her. When Faye called the next morning, the hospital told her Rick had been intubated and put into a coma late that night.

Coma

The eight-bed ICU at the Colchester East Hants Health Centre in Truro—a town with a population of about 12,000—is not often at the forefront of modern medicine. When Rick Cameron arrived on March 20, however, the hospital became home to the first critically ill COVID patient in the province.

The man in charge of his care was Dr. Kris Srivatsa, a 44-year-old internal medicine specialist with an easy smile and a swoosh of salt-and-pepper hair. Srivatsa had ended up in Truro almost by accident. Born in Mumbai, Srivatsa had relocated to the U.S. to finish his medical training. In 2009, with his visa running out, he’d desperately Googled “job opportunities in Canada” and stumbled upon a posting from a Nova Scotia town he’d never heard of.

Just a few months later he found himself driving deeper and deeper into what felt like uninhabited wilderness, second guessing his decision. But Srivatsa found an unlikely home in the community. He’d met his husband, an artist and gallerist, and they spent their vacations hiking Cape Breton Island. “It felt like a homecoming,” he says today. In 2015, he became a citizen.

In late February, as the mysterious new virus made its way across the globe, Srivatsa and his team began anxious preparations—creating a COVID unit, securing personal protective equipment and practising procedures.

The process of intubation—sedating a patient before inserting a nearly foot-long plastic tube down their windpipe—is a routine part of ICU treatment, but it had suddenly become perilous in the COVID era. There is a high risk of aerosolizing a patient’s saliva and respiratory secretions from their lungs and airways, sending the virus airborne. Srivatsa had been following the stories of nurses and doctors in Italy becoming infected and dying. He was determined not to see that happen in his hospital.

Rick had been immediately put on oxygen through a nasal cannula, a tube to his nose. But it wasn’t enough. He needed more than five litres of oxygen every minute to keep his blood oxygen levels above 90 per cent. His lungs simply weren’t drawing in enough air—he had to be intubated.

That night, the team in Truro carefully donned their personal protective equipment. Using the buddy system, team members watched each other put on gowns and gloves, N95 masks, face shields and hats until they were sweating beneath their armour. They sedated Rick, putting him into a coma. Then the anaesthetist approached. The key was to do it in one shot—any more attempts and you increase the risk of aerosolization.

The procedure went perfectly on the first try, and the team quickly worked to stabilize Rick. But the truth was, Srivatsa didn’t know how to treat his COVID patient. No one did. There is no cure for COVID-19. The most doctors can do is keep a patient alive and wait for the body to fight off the virus. Srivatsa and his colleagues were learning about the virus in real time alongside the rest of the world.

Srivatsa spent his evenings poring over the latest studies, reading about what had worked in other countries, looking for any clue that might improve the likelihood of Rick’s survival. A machine can do the work of breathing for a person for a little while. But at that point, early in the pandemic, the survival rate for people on ventilators was grim: up to 90 per cent of COVID patients on ventilators were reported to have died. (Later studies found that those early reports that Srivatsa had read were misleading, with the mortality rate more likely to be in the 30 to 50 per cent range.)

A Big Decision

In the days after Rick was diagnosed, Faye, Kelly and Brian each received their own positive COVID tests. The house became a divided sick ward. Faye was in the basement, suffering through her own chest congestion and fever, but thinking only of her husband. Each day was the same: she would wake up, sit in one little corner of the basement, and call the hospital. Then she’d sit and wait until it felt like a reasonable amount of time had passed before calling again.

With her dad unconscious in the ICU, Kelly started a Facebook page to let friends and family members know what was going on. It was a place for her to record their days—a diary she vowed her dad would read himself once he recovered. It was also a way to try to feel close to him at a time when COVID had forced families like hers apart, with hospitals still closed to visitors.

For Kelly and Faye, not being able to see Rick was the hardest part. For Srivatsa, too, having to share important news over the phone felt cruel and impersonal.

“Do you have access to Skype or some way that I can video call you?” he asked Faye one day. The doctor started a video call on his phone, and for the first time in weeks Faye was able to see her husband. “That was a turning point for me,” she says. She was able to put a face to the voices of all of the nurses and doctors who had been caring for him. And she could finally picture where her husband was—not in some strange void in the ether, but lying in a hospital bed, unconscious and shockingly thin, but still fighting, still her Rick.

After that, the family worked out a system with the nurses. They would do video calls with an iPad. Often a nurse would leave a phone on the pillow in Rick’s room for hours. Faye would tell him they loved him and say how well he was doing, even if the news that day had been bad. When she ran out of things to say, she would sing—songs by the Righteous Brothers and the Beach Boys, all the old classics she and Rick had listened to a lifetime ago, driving out to the rink in his Ford Falcon.

By week three, however, Rick was still in a medically induced coma, still testing positive for COVID. Srivatsa and his team adjusted his sedation. They tweaked the setting on his ventilator. But Srivatsa was getting worried. Rick’s body’s response to the illness had caused widespread inflammation. His creatinine levels were up, indicating a kidney problem. In a growing number of cases, those symptoms led to one outcome. “My goodness,” Srivatsa thought to himself one day. “After all this, he’s not going to make it.”

The doctors needed to get Rick’s lungs working. One way to do that was to put him in a prone position, turning him onto his stomach for a few hours before turning him back so that the back of the lungs, which had been compressed by the weight of his body, would be able to do their work.

Proning a grown man attached to a series of tubes and lines is a delicate, complex manoeuvre that takes a team of nine. Truro didn’t do the procedure in normal times; they sent patients to the larger hospital with more staff in Halifax. But these weren’t normal times. The move also came with serious risks: if something went wrong and Rick was destabilized and went into cardiac arrest, doctors might not be able to turn him back in time to save him.

When doctors told Faye she needed to decide if they should do the procedure, she burst into tears. That day, Faye and Kelly sat at either end of their large living room with Kelly’s brother Jeff on the phone, and talked through their decision. Suffering through the worst of her own illness, Kelly would fall asleep, then wake in a panic. Faye decided she couldn’t agree to anything that might endanger her husband. But that night, she couldn’t sleep. “What if I didn’t do the right thing?” she kept thinking. The next morning, she gave doctors the okay.

On April 3, Srivatsa and his team carefully followed the steps they had learned over video from doctors in Halifax. With three nurses on each side of his body, two respiratory therapists attending to the lines and ventilator at his head, and a doctor at his feet, the team turned Rick. Then they waited. Just a few hours later, the improvement was already evident: Rick’s oxygen levels were ticking up. He was finally beginning to turn the corner.

Sharing Progress

When Kelly started documenting her father’s battle with COVID, she just wanted to share his progress. But what had begun as a family page quickly grew into something much larger. The “papa bear” Kelly wrote about so movingly day after day became the face of an illness that was no longer a distant story. The local news covered Rick’s journey. Kelly’s posts were read by thousands, each message gathering hundreds of comments from people across the province and the continent.

On Easter Sunday, 25 days after Rick was hospitalized and nine days after the medical team first rotated him into a prone position, nurses called Kelly and Faye, excited to share some news: that morning, Rick had opened his eyes. They got Rick on the iPad, and there he was—still with tubes all over him, still so weak and fighting the sedation, but awake.

There were ups and downs, but steadily Rick grew better. Each day doctors put him into a prone position for a few hours. Each day they reduced the amount of oxygen on the ventilator, watching as his lungs became less and less dependent on the machine. The day they removed his tracheostomy tube, the nurses huddled around him. “Say something!” they urged. “Hi,” Rick croaked.

On April 26, 38 days after entering the hospital, Rick tested negative for COVID. A few days later, he was moved to the hospital in New Glasgow to start the long process of recovery. One morning he looked at his hand and felt a wave of terror as he realized he was too weak to raise it off the bed. He spoke to Faye and Kelly over the iPad, trying to make sense of what had happened to him. “How long have I been in here?” he asked.

Rick had been on life support for 35 days and had lost 45 pounds. But as his mind grew sharper, he became determined to get stronger. When the physical therapist asked him to do three minutes on a stepping machine, the next day he would do six. He became singularly focused on one goal: getting strong enough to get home to his family.

Srivatsa was no longer in charge of Rick’s care, but he couldn’t help but follow his former patient’s progress from a distance. “He felt like a family member,” says Srivatsa. When someone sent him a video of Rick doing physiotherapy, Srivatsa could scarcely believe it. Just three weeks earlier Rick had been comatose and intubated, a team of nine turning him onto his stomach. Now he was walking, shaky but determined, wearing a maroon hoodie emblazoned with the words “FU COVID.”

Home at Last

On June 3, Kelly’s 40th birthday and 77 days after Rick first entered the hospital, the family was finally able to bring him home. It was a cold and rainy day. When they arrived at the hospital, Rick was clutching a cane and wearing the same shorts in which he had first arrived. “He pretty near ran to the car,” says Faye. Rick hugged his wife. “Happy birthday, honey,” he whispered to Kelly, and they both burst into tears. As they pulled out of the parking lot, they gave a final wave to the nurses who were waiting by the entrance with tears in their eyes.

After two and a half months, the world outside the hospital walls seemed utterly transformed to Rick. People wore masks on the streets; “social distancing” and “flattening the curve” had become part of the lexicon; stickers marked where to stand at the local grocery store. It was a world in which an undercurrent of anxiety ran through the most basic human interactions. But in that corner of Nova Scotia, the pandemic had also brought people together.

As they turned onto the Camerons’ quiet street, Rick saw a strange sight: a woman he didn’t know on her front lawn, standing under an umbrella in the pouring rain, waving at him. Before he could make sense of it, the car pulled into the driveway, and he saw 40 people—neighbours and friends and complete strangers—surrounding his house, waving and cheering him on like a conquering hero.

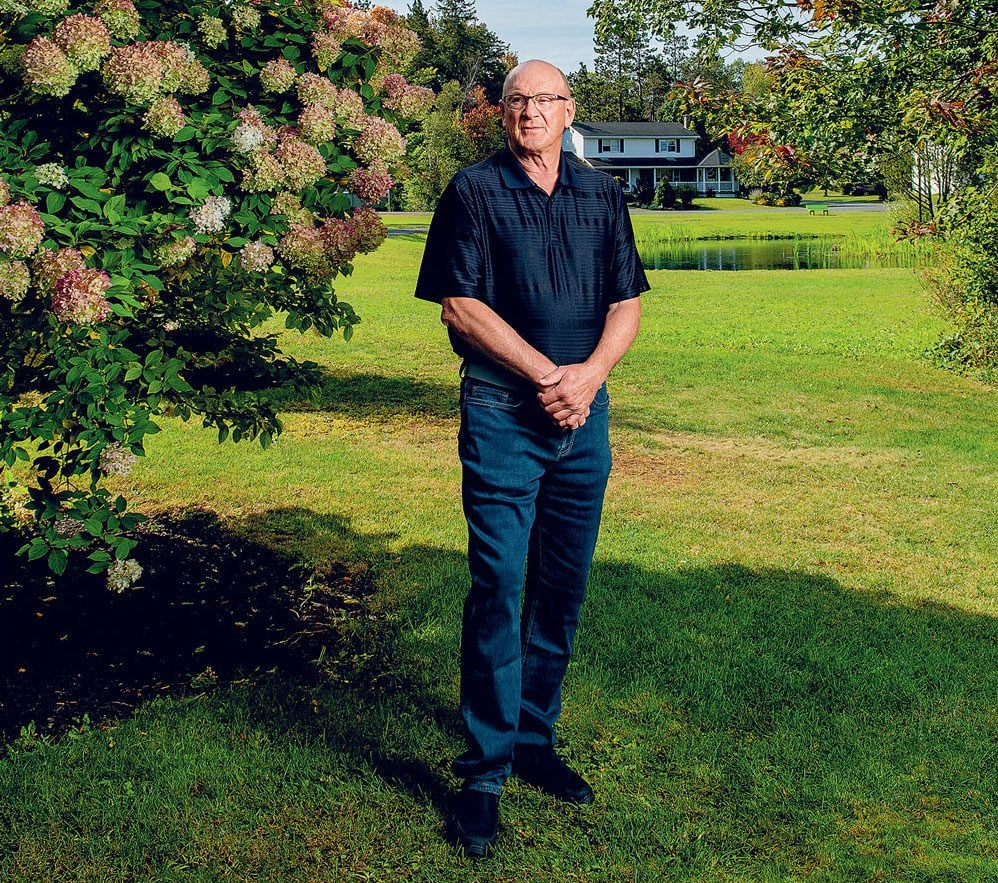

In the weeks and months since he’s been home, Rick is still trying to make sense of his experience. Each day he walks around the pond near their house, adding laps, gaining strength. He’s only recently been able to make it through Kelly’s Facebook posts, fighting back tears as he read the thousands of comments and prayers. It was strange to think about. If you added it up, all the people he’d met in his seven decades in that corner of Nova Scotia—the kids he’d coached, the co-workers he’d had a beer with, the countless hellos and pleasantries he’d shared in his personable way—Rick might have said he knew thousands. But to see all those people supporting him, willing him on, taking his personal survival as a symbol of hope in a dark time, that was almost too much to take in.

“I can’t walk up the street without cars stopping to talk,” he says. The other day a woman approached him at the local fish and chips place. “I know who you are,” she told him. She had been following his story for months. He was the man who’d seen the worst of COVID, nearly died, and walked out the door of the hospital.

Next, find out what it’s like to have a baby during the COVID-19 lockdown.