Of Furs and Fortune

In the summer of 1665, Médard Chouart des Groseilliers and Pierre-Esprit Radisson, two coureurs de bois from North America, sailed upriver on the Thames toward the sprawling metropolis of London. They had a business proposition to discuss with English financiers, after having been snubbed by authorities in New France and merchants in New England. The two men stood at the railing, sniffed the air, and smelled smoke as the buildings on the outskirts of the city drew near.

Mounds of rotting refuse were heaped outside the city gates, the whole place infested with small black rats—rats that were the hosts of fleas, and fleas that bore the bubonic plague bacterium. Plagues had ravaged the city every generation or so since the 1300s, but 1665 saw the worst outbreak in a century. At its height, in the fall of 1665, the Black Death killed more than 7,000 people each week in London alone.

The stench of death permeated the air, and carts lumped with corpses trundled down detritus-strewn roads. Clutching perfume-doused handkerchiefs to their faces, the duo continued upriver to the city of Oxford, where the royal court had fled to escape the pestilence. The men were taken ashore by Colonel George Cartwright, King Charles’s commissioner who had first met them when he was in Boston after the British conquest of New Amsterdam. Cartwright was astonished at the pair’s tales of a great sea that they claimed to have seen with their own eyes. He correctly surmised that the king’s financial advisors would want to hear their incredible tale and its promise of riches.

They disembarked and were taken for a series of interviews with prominent members of the royal court, culminating with an audience with King Charles II. Charles was a flamboyant hedonist known as the Merry Monarch because of the gaiety and social liveliness of his court. The son of Charles I, who had been beheaded in 1649 at the conclusion of the English Civil War, the younger Charles had spent 11 years in exile in France and the Dutch Republic while England was bowed under the weight of the dour and repressive Puritan rule of Oliver Cromwell. He had returned to become the king of England, Scotland and Ireland only a few years earlier, in 1660.

A man of good humour, fond of celebration, sumptuous furnishings and fine clothing, Charles was a subject of gossip, particularly for his numerous mistresses, seven of whom bore him a total of 12 children. But Charles was also an astute statesman, acknowledged for reviving the Royal Navy, reforming laws and taxes to encourage commerce and overseas trade, and supporting the arts and sciences. The Restoration period was the beginning of an age of unbridled optimism, ripe for new ideas and bold undertakings.

But Charles’s dissolute ways were a financial burden. His numerous mistresses and children and the maintenance of Whitehall Palace (then Europe’s largest, sprawling over 23 acres of grounds) were a great drain on the nation’s purse. Charles saw mercantile opportunities as a means to satisfy his insatiable desire for money to fund his grandiose dreams. The expansion of trade and commerce became national concerns, and the king formulated many of his national policies, including wars, through the lens of commerce.

He was also receptive to a plan that could make him money while damaging the prospects of the French, with whom England was frequently at war, by undercutting their trade from the St. Lawrence. The English knew that the prosperity of the French colonial outposts was based on a highly profitable trade in quality furs. Other members of the English court also perked up at the scheme put forth by the two French travellers, a scheme that promised to shaft the French in the fur trade while making a profit for themselves. The plan was the genesis of one of England’s most storied commercial enterprises.

Check out these gorgeous pictures of Canadian history.

The Kernel of an Idea

Although partners in many escapades, Groseilliers and Radisson were very different. They were brothers-in-law, one young and charismatic, the other grizzled and contemplative; Groseilliers was approximately 20 years older than Radisson. Both had spent the bulk of their lives on the fringes of French colonial settlement along the St. Lawrence.

A ship’s captain described Radisson: “Black hair, just touched with grey, hung in a wild profusion about his bare neck and shoulders. He showed a swart complexion, seamed and pitted by frost and exposure in a rigorous climate. A huge scar, wrought by the tomahawk of an Indian, disfigured his left cheek. His whole costume was surmounted by a wide collar of marten’s skin; his feet were adorned by buckskin moccasins. In his leather belt was sheathed a long knife.”

Groseilliers had first made his way to New France in 1641, when he was around 23. After the Iroquois drove the Huron from their traditional lands by the early 1650s, Groseilliers set out roaming west toward Lake Superior, searching for them in an effort to re-establish ties to the fur trade.

Radisson was between the ages of 11 and 15 when he arrived in New France in 1651. According to his own sometimes fanciful reminiscences, he was not in the community for more than a few months before he was captured by a roving band of Mohawk while out hunting birds. He was taken captive to their settlement along the Mohawk River in New York, a village of at least a thousand people in dozens of great communal longhouses surrounded by farms. Although the family was headed by a man who boasted 19 European scalps, young Radisson, owing to his facility with their language and his professed desire to learn their ways, was treated kindly and adopted. He learned to hunt and was trained in warfare before being taken on raiding forays against neighbouring peoples to the west.

But he longed for his former life. One day he was travelling with a hunting party of three Mohawk and a captive Algonquin. The Algonquin captive persuaded him to help kill the three Mohawk while they slept by crushing their skulls. “To tell the truth,” he admitted, “I was loathsome to do them mischief that never did me any.” Yet he nevertheless “tooke the hattchett and began the execution which was soone done.” The two quickly fled the scene of the murder, but after two weeks of travelling north through the woods, they were tracked down and recaptured by the Mohawk. The Algonquin man was quickly killed, and Radisson was saved only because he disavowed any role in the murders.

He again fled in 1653, but this time south along the Hudson River, and then successfully back to New France, where he met with his brother-in-law. Radisson, now in his early 20s and also an experienced traveller, convinced Groseilliers to hire him for an expedition planned for 1659. Radisson had grown accustomed to adventure and its attendant hardships and would never settle down to a conventional life.

Despite political opposition from various people in the administration of New France, Groseilliers secured a vague permit to leave the community and negotiated a profit-sharing agreement. When Governor d’Argenson demanded they take two servants with them, Radisson, suspecting they would hinder his movements and spy on his activities, replied insolently that he would gladly take the governor along, but not his servants, whereupon the governor grew angry and forbade him to leave Montreal.

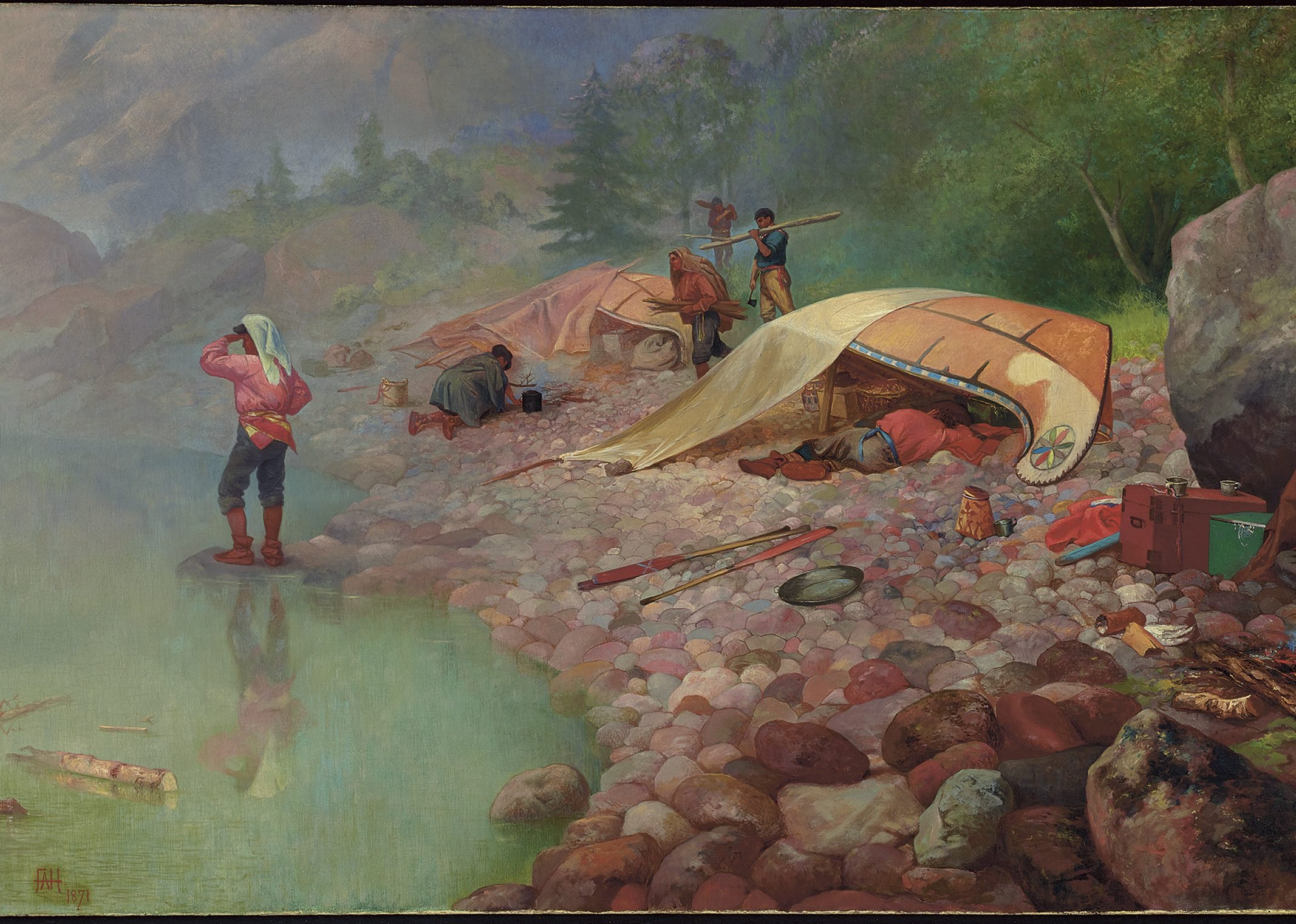

This was only a minor setback, and the brothers-in-law decided to leave under cover of darkness. When a group of Huron and Odawa offered to allow Radisson and Groseilliers to accompany them on their return journey west, to make a larger group for safety against marauding Iroquois, Radisson and Groseilliers agreed, and they secretly canoed up the Ottawa River and down the French River to Lake Huron and then west along the south shore of Lake Superior, following the well-travelled route. The two brothers-in-law and their Huron companions ranged far and wide in the Great Lakes region beyond the territory through which Europeans had ventured. The curious duo continued travelling west of the Huron lands along the south shore of Lake Superior and beyond.

They overwintered southwest of Lake Superior in what is now Minnesota, where they were invited to participate in a great “Feast of the Dead” celebration. Over 1,000 people came together in a great camp where the festivities included smoking ceremonies and ritual gift giving, feasting, drumming, dancing and singing, games and sporting contests. The two men now dug deep into their supplies for goods they had hauled all the way from Montreal and displayed them, both to trade and as gifts, an enticement for future trade. Many had seen these items from the east before, but not the strange people who produced them. Items presented by the Frenchmen included hatchets, knives, kettles, combs, mirrors, face paint and little bells and brass rings for the children.

From the Cree who had travelled from the northern forests they traded for the glossiest and largest beaver pelts they had ever set eyes upon, and heard tales of great rivers that flowed north to a frozen sea, a “salt sea,” perhaps the very sea that maps showed had been navigated by English mariners a generation earlier. Around campfires in the evenings they heard tales of massive herds of bison on the plains and “the nation of the beefe,” as they called the Sioux farther west.

The two travellers learned of the great trade fairs in the Mandan villages along the upper Missouri River. People from thousands of kilometres away, from all directions of the compass, congregated to haggle and barter for goods such as northern furs, pipestone, buffalo robes, grease, ochre, obsidian, eagle feathers, porcupine quills, fine leather, pottery, dried corn, wild rice, tobacco, dried herbs, preserved fish, precious stones, decorative seeds, coloured embroidery—and of course to share news of the land.

Radisson and Groseilliers formed the kernel of an idea that would eventually transform northern North America: they could tap into this well-developed intercontinental trade network that was lacking in certain goods—primarily metal tools, implements and weapons—that even now were not present in large quantities among the mix of goods generally available.

Learn about how Cree code talkers from Alberta helped win the Second World War.

A Mountain of Furs

In early summer the two travellers continued their journey by returning east, this time tracking the northern shore of Lake Superior and then canoeing downstream following rivers through the northern evergreen woodlands, travelling with parties of Ojibwa and then Cree over the established portages, trails and river systems. Groseilliers and Radisson were quickly realizing just how interconnected things were outside the orbit of the fledgling settlements of New France.

Along the shore of James Bay, near the mouth of what is now called the Rupert River, they came upon the rudimentary hut that the English explorer Henry Hudson had constructed in 1610, an “old howse all demolished and battered with boulletts.” If Hudson had been there before, ships could navigate there again.

The early English mariners from a generation or two before had been searching for the source of an inlet to a mighty inland sea or a route through the continent to the nearly mythical South Seas and the Spice Islands. What Groseilliers and Radisson found instead was an El Dorado of rich and thick furs from animals that lived in lands with long, dark winters and deep snows.

When the duo paddled back to the St. Lawrence on August 24, 1660, leading 60 canoes and perhaps 300 Indigenous traders, and loaded with a mountain of furs, they were celebrated as heroes. But Governor d’Argenson, out of jealousy and the intransigence of vested interests, insulted them as mere provincials and seized a good portion of their furs on the grounds that they had been trading without a licence. The adventurers retained barely one-fifth of their earnings, and Groseilliers was even tossed in jail briefly. Having claimed a large sum of their profits, the governor then promptly left for France that fall.

Spurned by their own government and annoyed at the corruption and restrictions on their activities, the two men set off for Boston—the next best place to seek sponsors for their grand and audacious scheme. That was where they met Colonel George Cartwright, who extended an invitation to cross the Atlantic and present their case to King Charles himself.

They had a plan that was sure to interest the English court: to use ships to exploit the vast beaver preserves surrounding Hudson Bay, bypassing New France altogether and dealing directly with the Cree who dwelt in the heartland of the beaver. Ocean-going ships could easily transport a greater quantity of furs than flotillas of canoes with time-consuming portages.

Perhaps they could even cut off the fur supply to the St. Lawrence, damaging French political and economic interests and making a profit for themselves in the bargain. It was almost too good to be true.

© Excerpted from The Company: The Rise and Fall of the Hudson’s Bay Empire by Stephen R. Bown. Copyright © 2020 Stephen R. Bown. Published by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: these are the 10 most famous shipwrecks in Canadian history!