“Let’s get this done before it starts pouring on us.”

Her feet hit first, striking the rock with the force of a hammer blow. Then she toppled onto her side, facing the cliff on a ledge barely wide enough to support her body. The rope at her waist snapped taut almost immediately, but she clung to a knob of granite in case it went slack again. The fall had happened so fast that she’d had no time to be frightened. Now she fought the panic rising in her chest.

Nine metres above her was the overhang from which she’d dropped. Two hundred and seventy-five metres below lay the floor of Death Canyon, a carpet of pines and brush strewn with house-size boulders. Her ankles were already swelling over the tops of her climbing shoes. Ants began to swarm across her legs; as she reached to brush them off, a bolt of dizzying pain shot up her spine. She wondered if her back was broken, too.

The clouds grew darker. And then it began to rain.

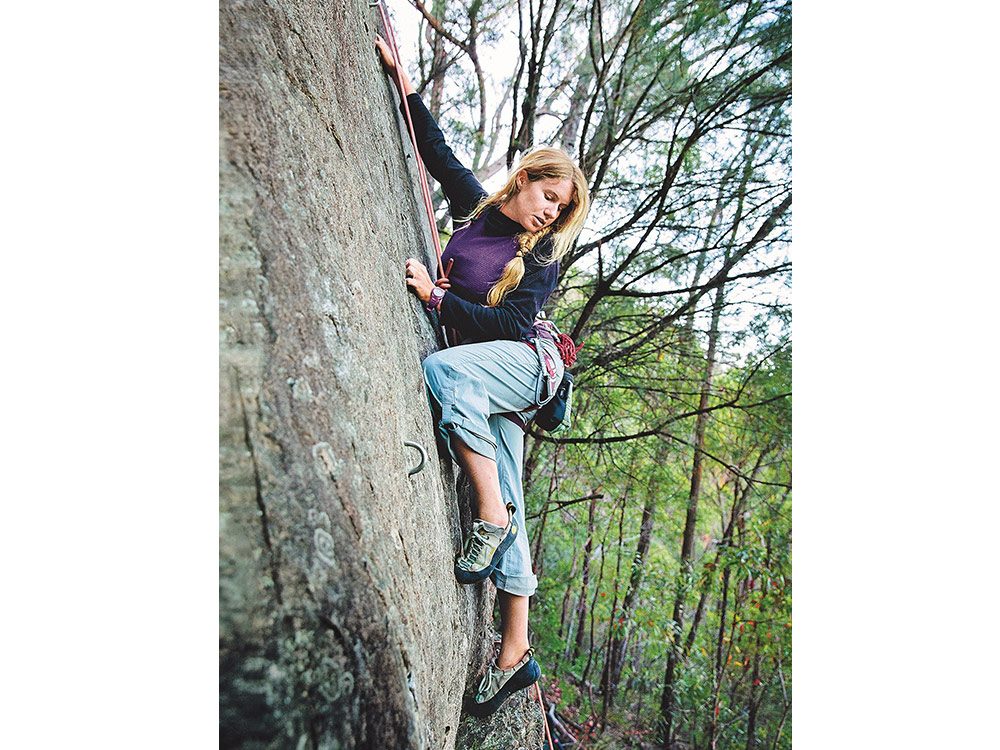

Growing up in a suburb of Portland, Ore., Lauren McLean spent vacations hiking, fly-fishing and horseback riding at her family’s lodge in British Columbia. In college, at the University of Montana, she took up rock climbing. After graduating, she spent a few months backpacking in Alaska and then took a summer job leading youth expeditions for Wilderness Ventures, an outdoor-adventure company in Wyoming.

On an outing with her students to a climbing spot in the Oregon desert, 25-year-old McLean met mountaineer and extreme-sports journalist Michael Ybarra. Ybarra, 44, had discovered alpine climbing in his 30s while working as a reporter for The Wall Street Journal. He had thrown himself into the sport, travelling constantly in search of new challenges. He was always ready to hit the rocks with another devotee.

McLean told Ybarra she’d be heading to the rugged Teton Range, in Wyoming, when her contract ended with Wilderness Ventures. “Let’s get together there to do some climbing,” he suggested.

In August 2011, McLean and fellow Wilderness Ventures instructor Dana Ries, 21, travelled to Grand Teton National Park, where Ybarra joined them. Both were eager to accompany him—he’d led technically complex climbs everywhere from the Himalayas to the Andes. The trio spent three days clambering up difficult rock faces. On Day four, they tackled the Snaz, a route on the south side of a formation known as Cathedral Buttress.

They started out at dawn, hiking through Death Canyon—so named because an explorer vanished there in 1899—to reach the base of the cliff. At 8 a.m., they stepped into their harnesses, tied themselves to nylon ropes and began the 548-metre ascent. It would take nine stages, called pitches, to reach the top, 2,926 metres above sea level.

Ybarra climbed first, threading his rope through metal cams that he jammed into cracks in the rock; such devices are meant to prevent climbers from falling too far if they lose their footing. When he finished a pitch, Ries and McLean followed, using the safety gear he’d left behind. Ybarra managed their ropes—a process known as belaying—reeling in slack until the women reached his position. Then he climbed the next pitch, and the cycle began again.

The day was gorgeous, and at first the going was smooth. But as the hours wore on, the group’s mood shifted from ebullient to grimly determined. The dark clouds that began gathering around 4 p.m. seemed to reflect the change in attitude. “We’d better hurry,” Ybarra said. “Let’s get this done before it starts pouring on us.”

One climber got stranded on Mount Logan for four days—here’s how she survived.

“We’re going to have to play this one by ear.”

There were two possible routes for the last pitch, which started from a narrow ledge. As was his practice, Ybarra opted for the harder one. It required the climbers to scale a three-metre overhang, clinging to the bottom before heaving themselves over the protrusion. As Ybarra ascended, the women could hear him grunting with effort. “If this is tough for him, we’re in trouble,” Ries said, exchanging a worried glance with McLean.

After Ybarra disappeared over the bulge, Ries tried to follow. She made it partway, then lost her grip and dangled from her rope. She and McLean discussed what to do as lightning crackled over a nearby peak. The pair knew they would be perfect targets if the storm came closer.

McLean pushed herself off the wall and dangled next to Ries. “Why don’t you try shimmying up my rope?” McLean said. “When you get to the top, tell Michael to lower me so that I can reach the rock and start climbing again.”

Grabbing her friend’s lifeline, Ries managed to haul herself to the granite protrusion a few metres above their heads. “See you soon,” she called, as she cleared the overhang.

Ybarra was sitting on a broad slab near the top of the buttress, where he’d anchored himself to the rock so he could safely belay his partners’ ropes. He seemed surprised when Ries turned up alone, and he winced when she informed him of McLean’s position. “We need to get her out of there before the wind shifts,” he said.

The women’s ropes ran through a fist-size gadget attached to the harness at Ybarra’s waist. Known as an auto-locking belay device, it’s designed to slow or stop a climber’s descent. Ybarra had rigged it to automatically clamp the rope if either woman fell; now he hurried to reset the mechanism, intending to lower McLean gently to the nearest ledge. Exactly what went wrong remains unclear, but in his rush, Ybarra somehow released the catch completely. As metres of rope shot out, Ries gasped and Ybarra’s eyes went wide. An instant later, he managed to apply the brake. He and Ries stepped to the edge of the slab.

“Lauren,” they shouted, “are you okay?”

Long seconds passed before the response came, in a quavering voice: “Not okay!”

Ybarra pulled out his cellphone and dialed 9-1-1; the dispatcher transferred him to a search-and-rescue (SAR) coordinator for Grand Teton National Park. “We’ve got an injured climber,” Ybarra told the ranger. “I’ll tell you more when I have the details.” Then he retied his own rope and began rappelling down the cliff. He found McLean nine metres below it, lying on a shelf of rock no more than half a metre wide. “I’m sorry, Lauren,” Ybarra said. “Something messed up with the belay. Where do you hurt?”

“Both legs and feet. And my back, whenever I try to move.”

“How bad is your pain, on a scale of one to 10?”

“Nine.”

“We’re going to get you taken care of,” he said. “But there’s no phone reception here. I’ll be back as soon as I can.”

Ybarra quickly returned to the top of the buttress. He called the ranger and described McLean’s condition. Then he handed Ries the phone for safekeeping and rappelled back down. “Would it help if I distracted you?” he asked McLean, dangling beside her. “Do you want to talk about your childhood?”

“Stay with me, but don’t say anything,” she said. “I need to focus on my breathing to keep away the pain.”

Ybarra fell silent and cradled McLean as she lay broken above the abyss.

Ybarra’s initial call reached Martin Vidak, the SAR coordinator. At 4:55 p.m., Vidak paged his fellow Jenny Lake Rangers—the specially trained 18-member squad assigned to Grand Teton’s Jenny Lake subdistrict. They gathered at the Lupine Meadows SAR base, a few kilometres from the accident site. And by 6:10, three of them had boarded the park’s helicopter for a reconnaissance mission to Cathedral Buttress.

The scouting crew brought back worrisome news: thunderstorms were nearby, and it wasn’t clear whether the angle of the cliff allowed enough rotor clearance—a minimum of nine metres—for the helicopter to extract the victim. Due to the late hour, she might have to spend the night there; the last rays of sunlight would be gone by 9 p.m., and safety regulations prohibited the chopper from flying after dark.

“We’re going to have to play this one by ear,” Vidak told his colleagues.

At 7:45 p.m., Dana Ries was sitting on the buttress, huddled against the deepening chill, when she heard the drone of helicopter rotors. Watching the ranger float down to her on a cable was “one of the most surreal experiences of my life,” Ries remembers.

“I’m Ryan Schuster,” he said, as the aircraft set him down with a large gear bag. He began inspecting the site and reinforcing the climbing anchors. Minutes later, the chopper returned and deposited another ranger, park medic Rich Baerwald. Then it came back with a litter full of medical equipment, food, warm clothing and sleeping bags.

Baerwald shouldered a backpack full of supplies, rappelled down the cliff, and reached McLean and Ybarra a little after 8:20. He checked her vital signs and splinted her left ankle, which was clearly shattered; if there were other broken bones, they could be set later. Ideally, the SAR team would get McLean off the rocks and to the hospital immediately. But with the approaching storm, fading light and narrow space for the helicopter to manoeuvre, the rescue would have to be quick and precise.

Baerwald radioed Schuster; both agreed the helicopter could squeeze between the rocks if the wind remained calm.

“I’m going to put you in a screamer suit,” Baerwald told McLean. “It’s a full-body harness that’ll support your spine until we get you on the ground.”

“Why do they call it that?” she asked. “You’ll see when you’re hanging from the helicopter.”

Ybarra helped strap her into the rigid suit, which had a ring at the front to attach it to a carabiner. With the chopper hovering above, Baerwald clipped McLean and himself onto the end of the rope. Together, they rose from the rock. McLean really did feel like screaming—but with joy, not fear. She was finally off the mountain. And the sunset was the most beautiful one she had ever seen.

These two pilots were flying from Oahu to Hawaii—then they heard the engines go quiet.

“Just go slowly and methodically, and you can get through it all.”

At the hospital in Jackson Hole, Wyo., McLean learned that she’d broken both of her legs and feet, her pelvis and a vertebra in her lower back. The damage to her left foot was so severe that the doctor told her it might have to be amputated. That night, a dose of morphine helped her sleep. The next morning, she was flown to the University of Utah hospital, in Salt Lake City, where she underwent four hours of surgery on the mangled foot. When she awoke, she was relieved to find it was still there. But the surgeons said it was too early to deliver a long-term prognosis.

Three days later, McLean’s father, the president of a small software company, drove her back to Portland; McLean spent her days in a hospital bed her dad had installed in the living room of his apartment. (McLean’s parents were divorced, and her mother had died the previous year.)

A month into her rehab, McLean asked her dad to put her old bike on a stand on his patio, which overlooked a grove of Douglas firs. An orthopaedist had told McLean she would never run again—never even walk up a steep hill. She decided to prove him wrong. Though both legs were still in partial casts, she pedalled every day. And when the casts came off, she threw herself into physical therapy.

In January 2012, six months after her accident, McLean took off for New Zealand, trekking in the countryside. By May, she was back to rock climbing in the mountains of Montana. And in June, she took another job leading youth expeditions—this time in Fiji, where she also learned to surf.

McLean’s goal of returning to the Grand Teton with Michael Ybarra will remain unfulfilled. Tragically, he died on a solo climb in July 2012, after falling from a 60-metre cliff in Yosemite National Park. “His death is still hard to process,” McLean says. “He was one of the strongest climbers I’ve ever seen.”

As for her own near-death experience, she says it simply made her more determined to live fully. “I try to keep a good attitude. Just go slowly and methodically, and you can get through it all.”

This scientist fell 20 metres into a crevasse and managed to climb out—with 15 broken bones.