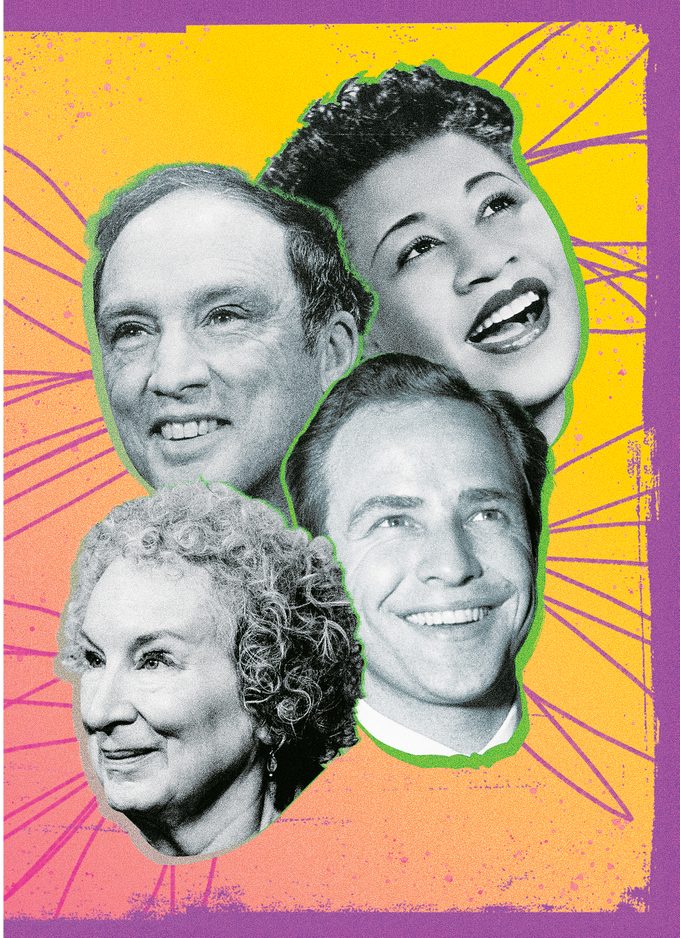

Hanging Out With Margaret Atwood, Marlon Brando and Pierre Trudeau

In this excerpt from his memoir, Canadian businessman Salah Bachir dishes about the humble private lives of his famous friends: Pierre Trudeau, Ella Fitzgerald, Marlon Brando and Margaret Atwood.

My lunch pal, Pierre Trudeau

My father always worried that I would be the one child out of five who would have trouble “making it,” and not just because I was gay or a rabble-rouser at university. He thought I wore my heart on my sleeve and cared too much.

Perhaps he finally thought I would make it after all when, in 1994, I told him I was going to have lunch with the person he admired most, Pierre Elliott Trudeau. And not just anywhere but at the Ritz-Carlton in Montreal.

I was going to figure out a way to make Trudeau pay for it, too. After all, our slogan at university was “Make the rich pay.” Long before Justin Trudeau became Canada’s 23rd prime minister in 2015, there was his father, the charismatic 15th prime minister, from 1968 to 1979 and 1980 to 1984.

The elder Trudeau introduced an omnibus bill that allowed abortion under certain conditions, decriminalized the sale of contraceptives, tightened gun laws and decriminalized homosexual acts performed in private. Although I demonstrated against some of Trudeau’s other policies—in a civil society, you discuss and debate your points of departure—I had long admired his intelligence, vision and quick wit.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau put Canada on the world stage. On my trips to Lebanon or China or even Albania, when I would say I was from Canada, everyone would smile and say “Trudeau.” Yes, that one. The sexy prime minister who drove people wild and inspired Trudeaumania. The one whose attempt to create a just society put him on United States president Richard Nixon’s bad side.

Trudeau was incredibly fun to watch, like the time a photographer snapped him at Buckingham Palace at the G7 Summit in 1977 while doing an impromptu pirouette behind the Queen’s back. England had Thatcher, the U.S. had Nixon and we had Trudeau. The contrast could not have been more pronounced.

I met him in 1994 at the video release of Memoirs, based on his book of the same title. We spoke briefly, and I told him I was coming to Montreal. (I wasn’t, but of course I would if he would meet me! Besides, I am a Montreal Canadiens fan and happily made the pilgrimage to the old Forum almost monthly during hockey season.)

I later followed up with a letter asking if he would meet me for lunch at the Ritz to discuss his memoir, although I mainly just wanted to tell him in person how much his famous statement about the state having no place in the bedrooms of the nation had meant to me.

I called on my friend, the politician Marcel Prud’homme, for help giving Trudeau another couple of letters from me asking to meet for lunch. Eventually, Trudeau agreed. But when we finally met at the Ritz-Carlton, he told me he was not in the mood for an interview. “Let’s just have lunch,” he said, and suddenly I was the one in the hot seat.

I jokingly asked whether the government had a file on me, considering I had run against him for Parliament as a Marxist in 1980. “Well, I’m sure they must have,” Trudeau replied. “There must be a few files on you and me here and there.”

He had me turn off my tape recorder and wanted to know everything about that time in my life. It was almost as if I were looking for absolution when I told him I received a full year’s credit in my political science class for my attempt to topple him.

“Yes, those university days,” he said. “Even some conservative politicians will tell you they were leftists or Marxists back then.”

He also asked about my charitable work, especially in the areas of HIV/ AIDS, and gay rights in Canada and the Middle East. He talked about hitchhiking through areas of Jordan I had not seen at the time. After that, we had lunch a few more times, though ours wasn’t the kind of relationship where I could phone him up and say, “Hey, Pierre, what are you doing this weekend? How about a canoe trip?” (Maybe because I couldn’t paddle or swim.)

At one lunch, I congratulated Trudeau on his appointment, back in 1984, of Canada’s first female governor general, Jeanne Sauvé. What a novel idea—an actual woman representing a female monarch!

“I adore her,” I said. “Hey, the next time you need to appoint a gay Arab, I’m available!”

“I’ll make a note of it,” Trudeau said dryly. “But you don’t strike me as the type to get up at six in the morning and fly out to open a school or community centre in northern Saskatchewan.” Great powers of observation, that one.

“Would I have to believe in the monarchy or in a higher power to be governor general?” I asked.

“Well, not believing in the monarchy, I think you can get away with that,” he said. “But I’m not sure I can sell the idea of an atheist governor general.”

“But imagine all the art I could put on the walls at Rideau Hall!” (Years later, when Adrienne Clarkson took the position, I donated a couple of paintings by Attila Richard Lukács.)

I met with Pierre Trudeau enough times that when I went back to the Ritz a few years ago, long after he had died in 2000, the maître d’hôtel recognized me—perhaps from my brooch, which identifies me better than a passport.

“Would you like to sit at the same table where you used to sit with Monsieur Trudeau?” he asked.

I would. I did. It was a booth in the back where you can survey the whole room, but no one can truly see you.

(Next: Check out this 2018 interview with Margaret Trudeau, about her book The Time of Your Life.)

Cooking for Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Fitzgerald would make me scrambled eggs in her kitchen—or I’d bring something over and we’d eat it in her backyard garden— but I think if I had known just how revered she was, I might not have been so relaxed around her.

Ella performed from the 1930s all the way through the ’80s, and she would come out on stage in an ordinary dress, too long or large on her, and wearing glasses so thick you feared she’d trip before she got to the microphone. Then she’d begin to sing, and her voice would take over and fill the room alongside the sounds of a full orchestra.

Duke Ellington once remarked that he had never seen musicians line up to hear a singer like they did for Ella. She had perfect pitch and a reputation for never doing a song the same way twice—except, of course, in the studio.

Frank Sinatra called her “the greatest popular singer in the world, male or female, bar none.” He also said she was the only singer with whom he was nervous performing, because he kept trying to reach her heights.

I met Ella, who was 40 years my senior, in 1978 through a mutual acquaintance, the publicist who managed Tony Bennett for 12 years and also helped manage Ella in Canada. He booked her into the Imperial Room, a 500-seat Toronto venue for big-name performers like Bennett, Louis Armstrong and Tina Turner. (Bob Dylan was infamously refused entry for not wearing a tie.)

“My uncle saw you perform in Baalbek in 1971,” I told Ella backstage. The Baalbek International Festival in Lebanon—with its dramatic backdrop courtesy of the Temple of Bacchus Roman ruins—is an experience no one forgets.

“You’re Lebanese?” she asked me. “Tell me, where can I find good kibbe in Toronto?”

That was easy: My mother’s kitchen. Kibbe is one of the national dishes of Lebanon and Syria. It’s made of meat and bulgur, baked or fried, with finely chopped onions and pine nuts.

Ella wanted kibbe? She would get it, and more. I asked my mother to make her some, and Mom went all out—not just kibbe but side dishes to go with it.

I saw to it that she used the finest ingredients in everything she made for Ella—better even than she would buy for our family. The fresh fruits and vegetables came from her garden, of course, but I searched specialty stores for the best cuts of beef, organic this and that, and then sat in the parking lot peeling the price stickers off my purchases. My mother never would have paid even half of what I spent on those pine nuts.

I brought Ella that food most nights while she was in town, which was up until 1986. If she was doing a two-week run, I showed up at her room at the Royal York Hotel with a different Lebanese dish on seven or eight of those nights. She didn’t like to eat right before a performance, but she needed to have a light meal, as she was diabetic. I have type 2 diabetes, too, so I knew that routine only too well.

It’s funny to reflect on it now. I was bringing kibbe to Ella Fitzgerald the way others might bring a photo for the star to sign. I didn’t always stay for the show—sometimes I went off to play hockey—but I managed to bring my parents on several occasions to see her perform.

Sometimes Ella would come over to my nearby apartment and just hang out after one of her performances. There was a privacy to it for her, I think, a feeling of relaxing rather than having to hold court at her hotel. She would sit around our table with a few friends and I would, naturally, serve a Lebanese dinner.

We’d have music blasting, sometimes Joni Mitchell’s albums Clouds and Blue, and sometimes I even played some of Ella’s old music. “I sounded good back then!” she would say with a laugh.

She repaid the hospitality by cooking for me at her grand, lovely home in Beverly Hills. She had a warm, joking relationship with her housekeeper; Ella credited laughter with getting her through so much in her life.

I loved her self-deprecating sense of humour. Once, when a reporter asked her what it felt like to be considered the greatest singer in the world, she responded: “Honey, you should go ask Sarah Vaughan.”

At her home, she would barbecue for us, with honey-drizzled fruit salad for dessert—but she always checked the glycemic index of everything she served, for her sake and mine.

I named my first dog, a Tibetan terrier, Ella. The dog went with me everywhere. My dogs have always mirrored my health issues; Ella the dog had kidney failure when I had kidney failure. “I do hope that dog learns how to sing,” Ella said when she learned of the four-footed Ella in my life.

I stayed in touch with the real Ella over the years as her diabetes took its toll, and last saw her in 1991 in Los Angeles. But she was always more concerned, in the best motherly way, with my own sugar levels. Late in life, she had both legs amputated due to diabetic complications and began refusing to see old friends.

I called to see how she was, and in her selfless manner, she asked if I was keeping my sugar under control. “You know, if you get the best wines and scotch, all you really need is one glass,” she said. “And keep away from the baklava!”

I could never figure out my fierce attraction to Ella. A friend asked whether I was like a son to her, but I don’t think so. I loved to hear her sing, of course, but it was more than that. She made everyone feel special and equal. There was none of the glamour and the trappings one might expect with the First Lady of Song.

(Read about secret signs of type 2 diabetes you might be missing.)

Marlon Brando in my mom’s backyard

“What can I get you?” my mother asked Marlon Brando. She wasn’t exactly sure who he was, other than some kind of actor, a new friend I had brought over for a backyard barbecue.

She would have asked the same question of anyone. In our family and in our Lebanese culture, one of the ways we show love is with food. A lot of it. Lots of love, lots of food. It wouldn’t have mattered if my mother had known who Marlon was, because she treated everyone with the same courtesy and hospitality—and anyway, to my mom, her kids were the stars.

Whether I brought over Ginger Rogers, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Elizabeth Taylor or any of the celebrities I befriended over the years, to her I was always the main attraction. The only time I shared the spotlight was when one of my siblings or their kids were also on hand.

My mother didn’t bring out the good china for Brando; she never used her good china for anyone. She had it there on display in the dining room buffet, one of those grand wooden pieces crafted in the old style.

It was 1989, and Marlon sat near the picnic table in my parents’ backyard, on one of our folding lawn chairs, that ’70s-style metal tubular variety with a fabric-strip seat.

There were vegetables growing on one side of the yard to disguise the chain-link fence that separated our house from our neighbour’s. Our vegetables were heavy on tomatoes, Lebanese cucumber and kousa—similar to zucchini and also known as Lebanese squash. There was also plenty of marjoram, sumac and the summer savories one can eat green or add to salads, and which, when dried, go into za’atar, a Lebanese spice blend that is suddenly all the rage everywhere but has been here all along.

Our family home was a three-bedroom house with a carport. It was located behind a strip mall on a dead-end street in Rexdale, a working-class neighbourhood in north Toronto. At the end of the street was the Humber River, where my two sisters, two brothers and I had played out our Tom Sawyer adventures. There was a big shed out back where Dad kept his tools.

My father was pouring a glass of arak for the man from On the Waterfront. “Did you know that your name is English for the Lebanese name Maroun?” he asked Marlon.

“St. Maroun, yes! I love that,” exclaimed Marlon, to everyone’s amazement. “The patron saint of the Maronite Church.”

Many Lebanese are Maronites. It was not the first time Marlon surprised me by coming out with something obscure, but he was a sponge for information that intrigued him. And virtually everything intrigued him.

“We’re not Maronites, we’re Greek Orthodox,” my father clarified to the Godfather over tabouli and fattoush salads.

“We’re not here to talk religion,” I interceded, heading that off.

I don’t think my parents would have acted any differently had they known their guest was one of the most revered actors of all time, a two-time Oscar winner. Not that I put much stock in awards. Who’s to say who is “the best” of anything?

We were all instantly in love with Marlon anyway. He put everyone at ease and tasted everything Mom made, complimenting her lavishly. A couple of times he asked, in French, for the names of certain foods in Arabic.

It seemed that Brando was up for just about any conversation, no topic off limits, but I purposely steered the talk away from his fame and acting career. It’s all on screen anyway, and I figured he’d enjoy a break from the endless questions—what was it like doing this or that or with this one or that one. I had no need to ferret out any of his secrets.

In the end, though, he learned all about mine because Brando was a person who somehow invited others to confide. I learned more about myself even as I was learning a little about the actor. It’s weird, but sometimes there’s a sense that you’d tell a stranger something you wouldn’t tell your closest friend, and I found myself opening up to Marlon about body image. I had become overweight.

He and I had that in common; we had both been in great shape at one point. Marlon’s weight famously ballooned over time, and Hollywood no longer offered him the good parts. Here he was, considered one of the finest actors of his generation, and he couldn’t get work because of his size. Like with so many of us in the world, the powers that be judged him by the pound. It was the same for Orson Welles and Elizabeth Taylor.

Marlon seemed to love the sense of family he saw in my childhood home—our unquestioned closeness. My siblings and I all stayed in Toronto, even once we were old enough and motivated enough to leave. When I had a major job offer in Los Angeles, I turned it down.

“We didn’t leave our land and homes in Lebanon and come here and learn a different language and do all those things just so one of you could leave,” my mom said. I took this as common-sense wisdom, not a threat. At one point, Mom and four of her five grown kids even lived in the same apartment building.

“How did they feel about you being gay?” asked Marlon.

“In a way, it was touching,” I replied. “My dad said, ‘Don’t tell your mom, she won’t get it.’ And when I admitted I’d already told her, he laughed. ‘Why would you tell your mother first? I’m your best friend!’”

Looking back now, I realize that Brando came into my life at a time of great uncertainty for me. There was AIDS and people were dying. There was a stigma around being gay, and people were being fired or shunned for it. I still needed to find my voice and my confidence, and here was this icon of the 20th century who was also struggling with body image and his place in the world, telling me he thought I was handsome no matter what size.

Over the years, I lost touch with Marlon. But one time, when I knew I’d be heading to L.A., I called and asked if he would be free for lunch and brought him an Inuit soapstone sculpture of a bear, similar to the pieces we’d seen together at a gallery in Toronto.

“I missed you,” he said. “Why didn’t you stay in touch?”

But you are Marlon Brando! I wanted to say. What could Marlon Brando possibly want with me?

It occurred to me that maybe it wasn’t just my parents who didn’t know who Marlon Brando really was.

Margaret Atwood: Bonding over birds

Just as you can run into famous actors on the streets of Manhattan, you can also run into the most renowned literary minds at a Canadian book-prize event.

Each year at the annual gala for the Giller Prize, I would see three powerhouse authors sitting in a row at a centre-front table: Margaret Atwood; her partner, Graeme Gibson; and Nobel Prize–winner Alice Munro. I would walk by that centre-front table and bow—not because they were literary royalty, which they were, but to acknowledge the spirit of creativity and perseverance they personify.

I certainly would not bow before any pope or king and queen. (I don’t recognize such titles. My grandmother always told me that everyone is important and no one is very important.)

Margaret Atwood is probably the only person around whom I choose my words carefully, or at least make the attempt. How can I not? I certainly realize the enormity of her output—more than 50 books of fiction, poetry, critical essays and graphic novels published in more than 45 countries. She has probably come out with a new book in the time it has taken me to compile this list.

With her boundless energy, she seems to have found the fountain of youth. Here she is at a demonstration. There she is helping to organize a fundraiser or writing a column defending the environment. She is always up on the latest events, and on language, politics and history.

She has more than two million avid followers on X (formerly Twitter). She always tells interviewers she “goofs off too much,” but I’m exhausted just hearing her schedule.

I had met Margaret Atwood many times in passing, but I got to know her better while helping to organize a gala in 2017 for her beloved Pelee Island Bird Observatory (PIBO), a welcome rest stop at the southern tip of Ontario for migrating birds, as well as an observational lab for studying migration patterns. She and her partner helped found it in 2004.

Sometimes people go directly to “Gala Salah” for my help raising money for good causes, and sometimes Gala Salah simply barges in and offers to make himself useful, which is how I came to emcee and co-chair the PIBO event.

After I introduced Margaret Atwood from the stage, she thanked the sponsors and attendees. “I never dreamed this could be done on such a scale,” she enthused. “It’s hard to raise money for a cause like migratory birds. It’s not like we’re raising money for some medical issue like kidney disease, after all!”

This met with polite applause from the audience. Back at the podium, I thanked her, adding: “Gee, Margaret, I rescheduled my dialysis so I could be here!”

This got a bigger response from the audience, many members of which had donated millions toward kidney research and to the Bachir Yerex Dialysis Centre at Toronto’s St. Joseph’s Health Centre. Founded in 2019, it was named for my husband, Jacob, and I, as we were major donors.

“No worries,” I assured the crowd. “If Ms. Atwood has not yet, she will be solicited later tonight.” And, of course, she came through with a donation.

What I learned that night was that Margaret never forgets. You do something nice for her just once, even the smallest gesture, and she repays it many times over. She is on a video tribute for my 65th birthday three years ago, singing “Happy Birthday.”

When she visited our apartment in Toronto, the concierge called up. “Mr. B., you’ve had some interesting people over, but this is really the Great One,” he said. In hockey circles, that would be Wayne Gretzky, but in overall star power, it’s Margaret Atwood.

She had arrived at the apartment that time to bring Jacob a birthday gift—a rare collectors’ edition of The Testaments, her 2019 sequel to 1985’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

“You’re one of the most significant futurists of our time,” Jacob told her—not to flatter her, just a statement of fact. It was a fact, and it was fair.

She spent the next several minutes rejecting the label of “futurist.” By the time she wrapped up her thoughts on it, after summing up a few of her story narratives, she conceded: “Oh, well, maybe I am a futurist.”

Later, to welcome me home from the hospital after my kidney transplant in 2021 and subsequent series of medical traumas, she sent the most gorgeous bouquet of flowers and regularly checked in on me from her world tours. Not only will she lend a hand if asked, she will suggest other people to approach, or will approach them on your behalf.

Sadly, her partner fell prey to dementia and died in 2019 while accompanying her on her book tour to promote The Testaments. Margaret had decided to take him along so that they could stay close and share her success.

When the two were at my Toronto apartment for dinner one time, what impressed me most was how they interacted, with intelligence and low-key humour, despite the progression of his disease. She allowed Graeme to be Graeme in a way we never really see in a society that shields age and impairment from the collective gaze. It was such a tender way to see them.

It’s still crazy to me to think that I was reading Margaret Atwood in high school—she is only 16 years older than I am—and that I’d wind up being friends with her all these decades later.

When I marched in demonstrations when I was younger and had no money, and had only my dad’s broken-down Delta 88, I kept a list of three people I could call in case of emergency—to pay for a tow or for bail.

If I had such a list today, Margaret’s name would be on it.

Excerpted from First to Leave the Party by Salah Bachir with Jami Bernard. Copyright © 2023, by Salah Bachir. Published by Signal, an imprint of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.