The Missing Daughter

New Liskeard, Ontario | 1996

A teenager decides to walk home alone and is never seen again

Nothing bad seemed to happen in New Liskeard, a small lakeside town in northeastern Ontario, until one September evening in 1996, when Mélanie Ethier—a 15-year-old who had recently told her best friend she wanted to become a teacher—went to her friend Ryan Chatwin’s house to watch the thriller Sudden Death. Around 1:30 a.m., Ethier said good night. On another day, she likely would have called home for a ride, but her house’s land line had been cut off; her family was behind on the bill. So she chose to walk alone. It was roughly a kilometre to her house.

According to one unproven witness account, when Ethier crossed a bridge along her route, two men pulled up beside her in a car and, after talking to them, she got in the car and it drove away. The next morning, her mother, Celine, discovered that Ethier never made it home. She reported her missing later that day. The town went on high alert. Police questioned Ethier’s friends and relatives. Volunteers combed the area around her route. A search-and-rescue unit checked the river. No one could find her.

Over the following years, police received 700 tips from more than 500 people. Theories abounded: that her father had kidnapped her (he wasn’t even in town at the time); that she’d been killed by a man named Denis Léveillé who, at the time of Ethier’s disappearance, was dating her mom’s friend (he had allegedly previously assaulted another teen girl); or that it had been white supremacists (Ethier was one of the few Black girls in town).

Yet no suspect was charged. In 2021, an episode of CBC’s true-crime podcast The Next Call inspired a new witness to come forward. For reasons that police won’t disclose, the man pointed them to a wooded area 10 kilometres from Ethier’s last known whereabouts, and in October, police searched it with dogs and drones. Still, no answers.

Celine accepts that her daughter is dead, but she hasn’t given up on finding her body. “Then I feel I’ll be able to move on,” she has said. “I believe Mélanie deserves to be found. She’s not just garbage that you throw to the side of the road.”

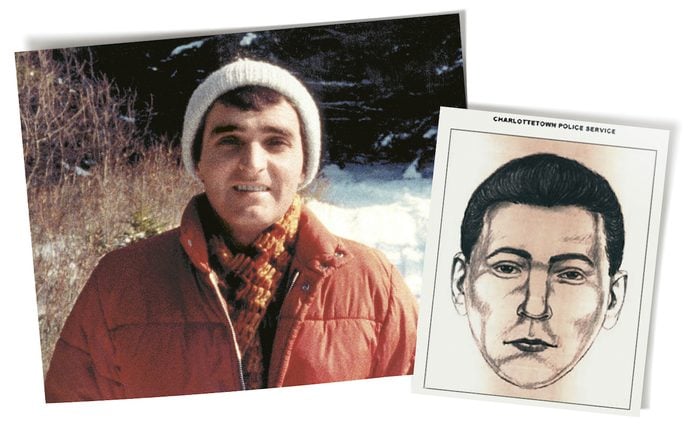

The Island Murder

Charlottetown | 1988

A terrified community and a killer who promised to strike again

Around Charlottetown, Byron Carr was known as a caring schoolteacher, a gracious dinner party host and a lover of rock ’n’ roll. On the evening of November 10, 1988, the 36-year-old had some friends over for coffee and then went bar-hopping. As he was driving home alone in the early morning hours after dropping off a friend, he reportedly stopped next to a young man riding a bicycle in the road. The two spoke for a while, and then Carr drove off. The cyclist appeared to follow in the direction of Carr’s home. That was the last time anyone saw Carr alive.

When Carr failed to show up to a family function the next day, his relatives visited his house to find his door ajar and his lifeless body on the floor in his bedroom, strangled and stabbed. His wallet had been stolen, and on his wall, someone had written in pen, “I will kill again.”

Based on the scene of the crime, police suspected that Carr had been killed following a consensual same-sex encounter, perhaps with the man on the bike. Some believe the nature of the murder hindered the case. In a foreshadowing of the police failures in the case of Bruce McArthur, the serial killer who preyed on gay men in Toronto’s Church-Wellesley neighbourhood in the 2010s, Charlottetown’s gay community accused the police of treating Carr’s murder with indifference. Gay men and women told media they also feared speaking out, lest they out themselves or become the killer’s next target.

For nearly two decades, the investigation went nowhere. Then, in 2007, police reopened the case. A witness reported that a couple of months after Carr’s murder, a sexual partner matching the profile of Carr’s killer had become violent with him in his Charlottetown home, stolen his wallet at knifepoint and said he’d done this before.

In 2018, the case again evolved. An anonymous informant called police in July from a payphone at a mall in Charlottetown, suggesting they had a tip to deliver about the Carr murder. The source hung up before divulging any info, though, and police later put out a call encouraging him to come forward again to share what he knows. If Carr’s murderer is still on the loose, it could save someone’s life.

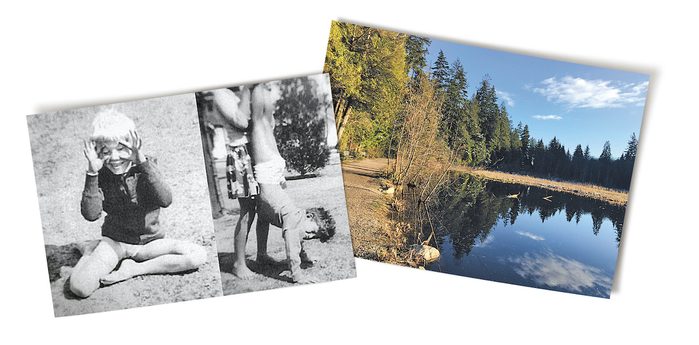

The Babes in the Woods

Vancouver | date unknown

The identities of two murdered children haunted investigators for years

In January 1953, a groundskeeper made a horrific discovery in the brush of Vancouver’s Stanley Park. Hidden under a woman’s coat were the bodies of two young children. Investigators found a wealth of evidence—a hatchet, a woman’s shoe and two aviation caps—but nothing to identify the kids. They determined the children had been killed at least five years prior, although a doctor at the time misidentified them as a boy and a girl. The mystery made national headlines and tips flooded in, but none yielded answers, and no parents came forward to report them missing.

New clues emerged in the ensuing decades. One witness recalled a one-shoed woman stumbling out of the Stanley Park bush about five years before the discovery; another told of meeting a woman and her two sons, at least one of whom was wearing an aviation helmet. In the 1990s, Vancouver sergeant Brian Honeybourn reopened the case and took the remains to a specialist who extracted DNA, determining that the children were, in fact, both boys. Honeybourn cremated their remains, saving some crucial bones, and scattered their ashes in the ocean. It seemed like their identities were doomed to remain a mystery.

Then, 70-plus years after the boys’ deaths, a breakthrough. Last May, Vancouver police enlisted the help of Redgrave Research Forensic Services, a Massachusetts firm that has helped solve several high-profile cold cases, including identifying the Ontario man who killed nine-year-old Christine Jessop in 1984. A Lakehead University lab extracted genetic material from the boys’ bones. Scientists in Alabama sequenced the DNA and then sent it to Redgrave to compare the results against genealogical databases. They got a match: one of the boys’ maternal grandparents. From there, they found the boys’ sister and great-niece, who still lived in Vancouver.

In February 2022, investigators publicly identified the victims as seven-year-old Derek D’Alton and his six-year-old half-brother, David. Police theorize the killer was likely a close relative who died approximately 25 years ago but have yet to name anyone with certainty. “These murders have haunted generations of homicide investigators,” Vancouver inspector Dale Weidman said in a news release. “We are relieved to now give these children a name and to bring some closure to this horrific case.”

These true crime movies will chill you to the bone.

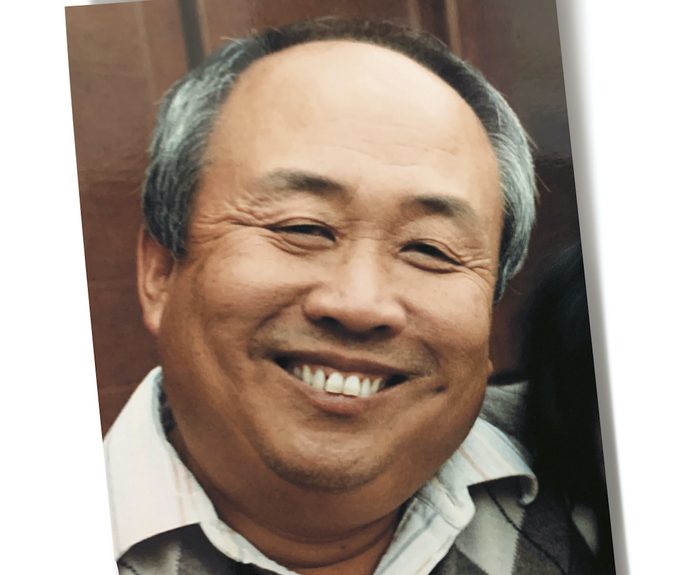

The Robbery Turned Deadly

Toronto | 1993

The search for the teenagers who shot a beloved store owner

Suck Ju Ryu emigrated from South Korea to Canada in 1972 with little more than a dream of a new life. With his wife, he raised a family and, about a decade later, opened a new convenience store on the ground floor of a seniors’ home in the north end of Toronto. The residents and other locals got to know the soft-hearted and hard-working business owner. By the cash register, the linoleum tiles had worn away from the years he’d spent tending to the store.

Sometime during the afternoon of February 18, 1993, 56-year-old Ryu closed the store briefly to drive his wife home, as he often did. Shortly after he returned, two teen boys, believed to be 15 and 17, reportedly entered the store with a firearm. Ryu’s daughter and police suspect he refused when the teens demanded he hand over his cash. Whatever happened, one of them shot him in the chest and they fled. A few minutes later, a customer found Ryu lying on the floor and called 911.

The suspects were last seen boarding a westbound bus, but by the time the police caught up to the vehicle, the teens were gone. Police canvassed the neighbourhood, collected evidence from the store and brought the bus in for forensic examination. But with no solid leads or security footage, and with DNA technology still in its infancy, they couldn’t zero in on the killers.

In 2021, nearly 30 years after Ryu’s murder, Toronto police reopened the case in the hopes of extracting DNA and further evidence from what was collected on scene, hoping that advancements in testing technology might crack the case. The force also promised to create a profile that they can compare to a database of known offenders. Ryu’s daughter Elizabeth is still hoping for a breakthrough. “There are moments where I might see someone walking by who looks like my dad and my heart stops,” she told media. “And then I realize it’s not him.”

Here are 20 Netflix Canada documentaries worth watching.

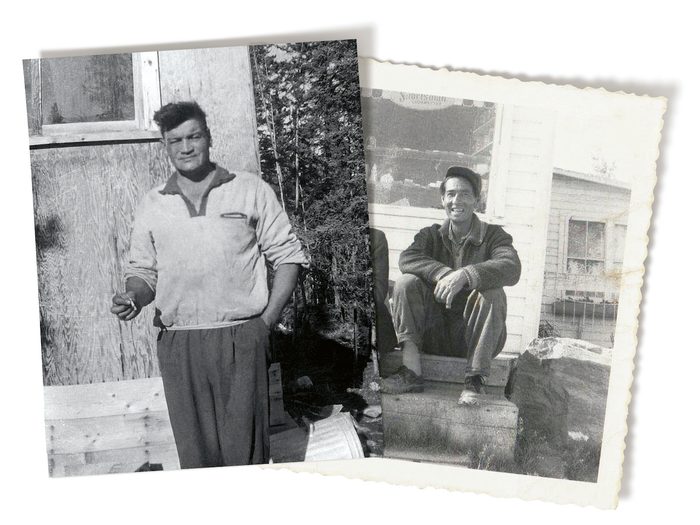

The Prospectors Who Never Returned

Saskatchewan woods | 1967

The RCMP ruled out foul play—but family and friends disagree

In June 1967, 59-year-old Métis leader James Brady and 40-year-old Cree band councillor Absolom Halkett boarded a tiny plane and departed the small Saskatchewan town of La Ronge. From there, they flew north to a remote lake on a trip to prospect for uranium. By the time another plane arrived to restock their camp about a week later, the men were gone. The RCMP investigated, but neither the men nor their bodies were found. Police quickly ruled out foul play and closed the case within weeks. The best guesses to come out of the investigation: the men had gotten lost or been eaten by a bear.

To those who knew Brady and Halkett, however, those weren’t plausible explanations. Both were experienced bushmen; they wouldn’t just vanish. And why had the investigation wrapped up so quickly? In a recent book, Cold Case North, author Deanna Reder writes that her mother, who knew the men, said they were taken by a UFO—to her it seemed more logical than any of the other theories. Others suspected the men’s deaths were no accident, but assassinations. Brady specifically was an ardent communist who challenged the Canadian government and the church, advocating for First Nations’ self-governance; back then, it was enough for the RCMP to surveil a person. Some even suspected they found a uranium site and were killed by business partners who wanted it for themselves.

In the past few years, the bodies of what appears to be the two men were discovered. An American tourist and fishing guide found a waterlogged corpse with its wrists tied in the water where the men had been prospecting. Reder and her co-authors later found evidence of what could be human remains at the bottom of the lake, though it remains inconclusive. Their book proposes, but doesn’t confirm, a prime suspect: another fishing guide with a history of violence. Indigenous filmmakers Danis Goulet, Tasha Hubbard and Shane Belcourt have now optioned the book for a film, which could renew interest in the case and finally lead to conclusive answers.

Delve deeper into Canada’s most baffling unsolved mysteries.

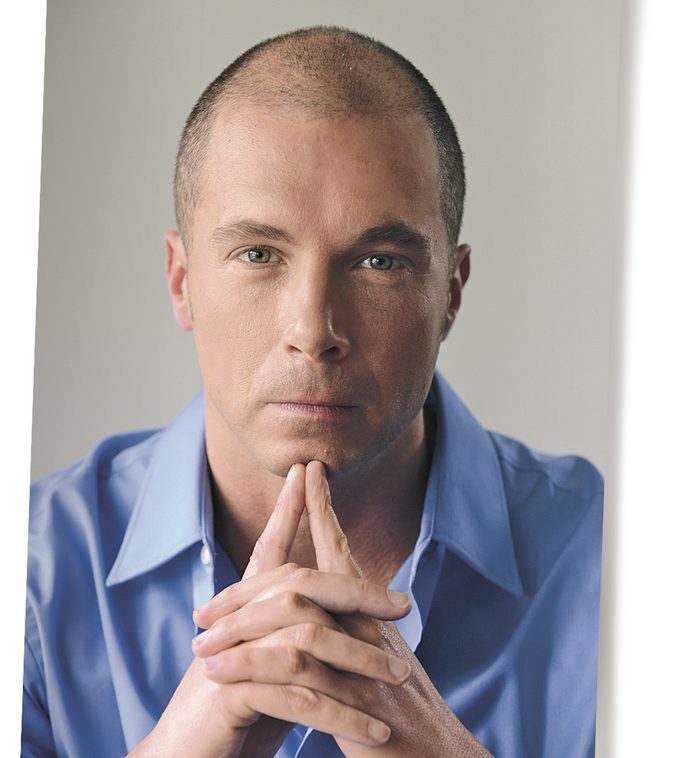

Cracking cold cases with criminologist Michael Arntfield

Reader’s Digest Canada: How did you become interested in cold cases?

Michael Arntfield: As a child in London, Ontario, I walked to school along the same path as a boy who was abducted and murdered by a serial killer who was known to be at large. Many years later, when I became a detective constable with the London police’s criminal investigations division, the first major cold case task force was up and running. I began looking into cold cases as a sort of hobby.

In 2013, you became a tenured professor at Western University, where you created the Cold Case Society. What kind of work does it do?

The society started as a class on serial homicide. I put students into groups and asked them to explore potential new investigative avenues for a certain cold case. If their reports were compelling enough, we’d turn them over to the relevant investigative agency, police department or the family or family lawyer of the victim. There was so much interest from students across the university that we started the society.

What has been your most significant breakthrough to date?

One big one is the case of Joe Grozelle, who died as a cadet at the Royal Military College about 20 years ago. The military police ruled it a suicide, but it was fishy; he was unaccounted for more than two weeks before his death. The society took it on and wrote a report, and the chief coroner has since reopened the case and ordered a homicide investigation.

How do you decide which cases to re-examine?

One interesting way we find cases is through the Murder Accountability Project, which is run by a group of homicide scholars who collect data on murders in the U.S. I sit on its board. The organization has access to a database of killings, as well as an algorithm that scans cases coast to coast looking for commonalities. For example, if we see two or more female victims have been strangled in the same area, and the cases are unsolved after a year, that’s flagged. Then a few members of the society might work on it for weeks or months until they’ve exhausted every avenue.

What attracts people to this work?

There are questions I think anybody with a sense of social justice wants to answer: Why did this happen? Who would do this? Why is it still unsolved?

Michael Arntfield’s new book, How to Solve a Cold Case, is out now.

These two retired officers teamed up to solve a 55-year-old murder

In the summer of 2017, retired forensic investigator Gord Collins moved to Muskoka, a swath of cottage country in Ontario. There, he met Linda Gillis Davidson, a former RCMP inspector. Instant friends, they shared a mutual fascination with cold cases—and decided that, just maybe, they had the time and skill required to solve one.

The duo have dedicated themselves to decoding the disappearance of Marianne Schuett, an 10-year-old from Burlington, Ontario, who vanished while walking home from school in April 1967. In the days after, roughly 18,000 people participated in an unsuccessful ground search. Police later identified a main suspect, an alleged serial sexual predator who died by suicide as officers closed in on him in 1991. At the time of her disappearance, Collins, then 14, lived nearby. “It was shocking to me that this could happen,” he says. “I never forgot her face.”

Collins and Gillis Davidson have now spent years interviewing family members, neighbours and classmates, as well as retired investigators and another of the suspect’s victims (who escaped before he could abduct her).

In 2021, a set of clues led the duo to two sites surrounding a defunct quarry near Acton, Ontario. They hoped to find the location of Schuett’s remains.

When they searched the first site, several cadaver-sniffing dogs zeroed in on the same tree. At the second site, the dogs again focused on one spot: a rock wall located near the driveway of an abandoned farmhouse. They now suspect they likely stumbled on Schuett’s killer’s dumping ground. “We got goosebumps,” says Collins. “The hairs on our arms stood straight up.”

To test their theory, they’ve collected numerous soil samples, from which a lab is now trying to extract human DNA. If they’re successful, the two will compare the biological information to samples provided by Schuett’s family—and perhaps the DNA of other victims. “It may or may not be Marianne,” says Collins. “Either way, we have a lot of work to do.”

Find out how a retired cop is reheating cold cases in Halifax.

How forensic genealogy is revolutionizing criminal investigations

In 1986, police in Leicestershire, England, approached genetics professor Alec Jeffreys with an unusual request: could he identify the man who had raped and murdered a 15-year-old girl? Jeffreys, who had earlier discovered that humans can be differentiated by patterns in their DNA, agreed to help. The police supplied over 4,000 samples of saliva and blood from men in the area for Jeffreys to analyze. Within a year, he had found the killer.

Following the case, police departments around the world began using DNA analysis to catch perps. “It was an investigative game changer,” says criminologist Arntfield. In the 1990s, he says, you’d need a large sample—for example, a vial’s worth of blood—to yield enough DNA to conduct an analysis. Today, testing technology can extract DNA from a single strand of hair or the skin cells that are left behind when someone touches a surface.

This has led to a revolutionary new discipline called genetic genealogy. Using this method, investigators compare DNA extracted from a crime scene against genealogical databases, such as banks of convicted offenders’ DNA or biological information submitted to websites like 23andMe and Ancestry. Next, investigators can often narrow their search from millions to just a few persons of interest. They then acquire their new suspect’s DNA by, for example, retrieving a discarded coffee cup. This practice has resolved dozens of mysteries, including the identity of the Golden State Killer, a man who killed at least 13 people in California and is responsible for at least 45 rapes.

Yet forensic genealogy is dogged by privacy concerns. Few people who submit their DNA to ancestry websites likely realize they may also be allowing law enforcement to snoop in on their genetic code. As such, in both Canada and the U.S. police often now need a judge to sign off on a warrant to access private companies’ databases. Many forensics experts argue, however, that privacy shouldn’t impede the greater good—that is, catching criminals.

For more on cold cases in Canada, check out these chilling true crime podcasts.