He didn’t mean you—keep your shoes on!

In 1920s Germany, two brothers named Rudolf and Adolf Dassler founded their own shoe company, then called “Dassler Brothers Shoe Factory.” Though the two brothers didn’t always see eye to eye, they were able to put their differences aside and work together—until one night during World War II. Rudolf and his family were in a bomb shelter during an Allied bombing raid when Adolf joined them. The first thing Adolf said was “Here are the bloody bastards again,” referring to the bombers. Rudolf, though, assumed that Adolf meant him and his family, and no one could convince him otherwise. From then on, their relationship went from bad to worse. He refused to work with his brother, and after the war, they dissolved the business and each formed their own companies. Adolf named his after himself, combining his nickname, “Adi,” with the first three letters of his last name. Rudolf originally called his “Ruda,” but then tweaked it to share a name with a certain wildcat. Today, the rivalry between Adidas and Puma remains (though it’s much friendlier). Here are 11 more famous sibling rivalries throughout history.

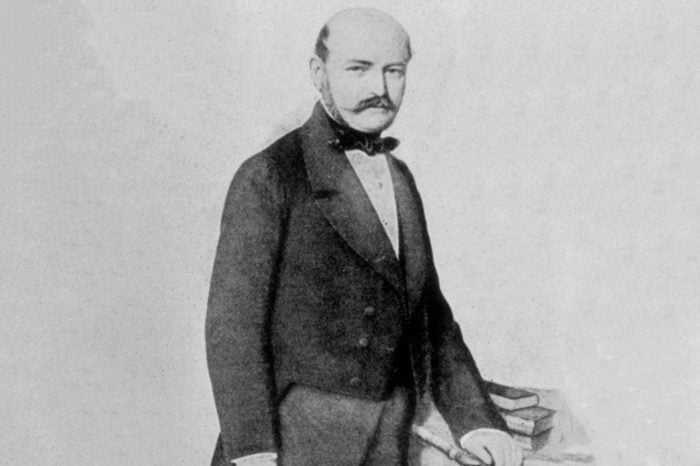

(Male) employees must wash hands

In 19th century Vienna, Austria (then Austria-Hungary), a Hungarian doctor named Ignaz Semmelweis got a job at the hospital’s maternity clinic. He noticed something troubling: in one ward, where doctors and medical students—all male—were in charge, many new mothers were dying from “childbed fever,” which was not the case in the other ward, run by female midwives. Semmelweis puzzled over differences between the wards, trying to find an explanation. He realized that the doctors, because they were doctors, were also conducting autopsies—and often wouldn’t disinfect their hands between visits to the morgue and the maternity ward. He insisted that a good, thorough scrubbing with chlorine solution was all it would take to stop the deaths. But the doctors refused to believe him. In a prime example of literal toxic masculinity, the doctors decided that the hands of “gentlemen” couldn’t possibly be unclean. Semmelweis began to grow outright hostile to his critics, and the head of the maternity ward teamed up with a particularly outspoken doctor to fire him. Had they simply accepted Semmelweis’ findings, the medical community could have accepted the value of hand hygiene more than twenty years before Louis Pasteur.

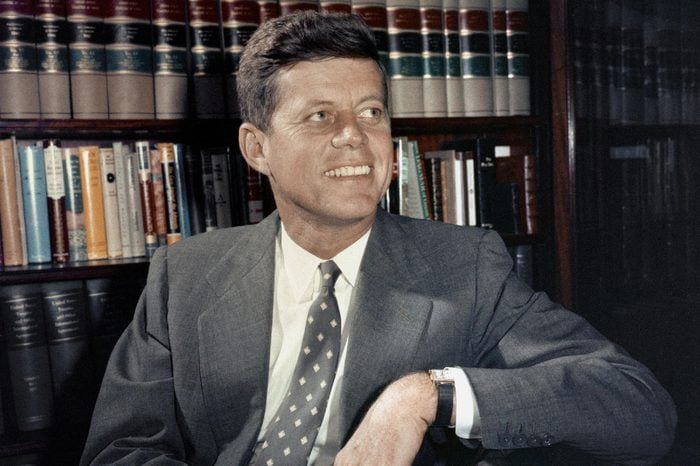

Presi-don’t be like that

The story of American politics after John F. Kennedy’s assassination is one of two men in the same party who just couldn’t get along. The feud between Lyndon B. Johnson and Robert Kennedy had begun long before that day; historians agree that their mutual dislike existed since the day they met. Johnson had been actively outspoken against the Kennedys’ father, Joe, and Robert had no interest in associating with him. The first time they met, on RFK’s first day in the Senate in 1953, Robert refused to shake Johnson’s hand. After John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, small incidents began to escalate into a huge behind-the-scenes animosity. Almost immediately after learning of JFK’s death, Johnson called Robert from Air Force One, asking to know how the swearing-in process worked. When the plane landed in Washington, Robert gave the new president no acknowledgement whatsoever. Their supporters started playing the blame game and spreading conspiracy theories about the other candidate. By the time the 1968 presidential race rolled around, and Robert chose to run against the incumbent president, much of the country was in turmoil over the Vietnam War, and Johnson decided that he could extend the feud no further. He dropped out of the race, and Robert’s subsequent assassination left the Democrats with no one to rally behind. Had either of those men remained in the race, America may never have seen a Richard Nixon presidency.

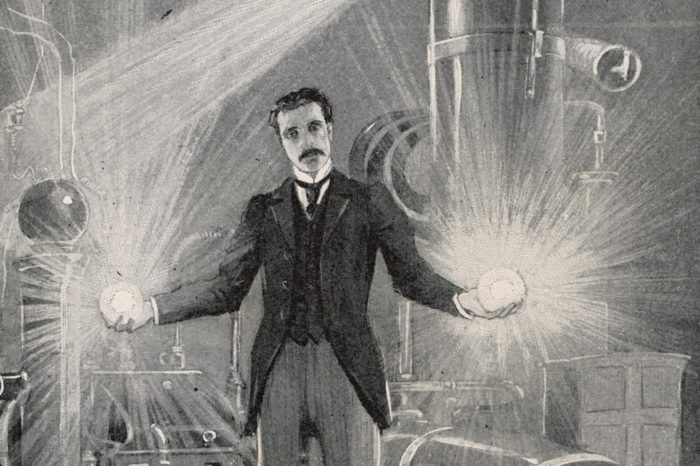

It’s electric

You know that great inventor, the one who’s primarily responsible for electricity as we know it today? No, not Thomas Edison. In the late nineteenth century, a Serbian immigrant named Nikola Tesla began working for Thomas Edison, who was already famous for “inventing” the light bulb (whether he actually did so is quite debatable). Tesla had an idea for an alternating-current (AC) system that would channel electricity many times in different directions. Edison, though, had already spent lots of time and money developing a direct-current (DC) system and had no interest in furthering Tesla’s idea. No longer working for Edison, Tesla sold a patent for AC to Westinghouse Electric Company, the primary rival of Edison’s company. AC was much more cost-effective—and effective, period—than DC, and that made Edison nervous. So he did his best to sabotage its path to dominance. He launched a fear-mongering campaign, trying to convince people that AC was incredibly dangerous. He even paid an electrician to produce an electric chair using AC. However, for all his efforts, AC’s overall superiority won out, and Westinghouse’s AC generators were installed throughout the country. Historians, however, believe that Edison’s smear campaign is likely the reason Tesla is not a household name. Today, this feud is so famous that historians have dubbed it “the war of the currents.” Check out these other history lessons your teacher lied to you about.

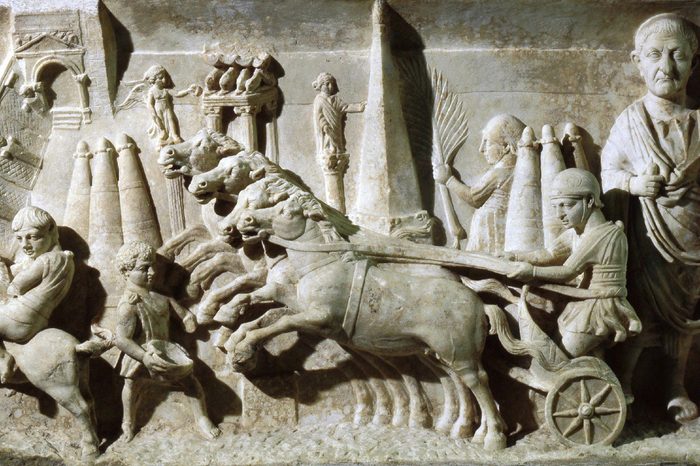

The original color war

If you thought your enmity for your rival sports team was bad, you should’ve seen first century Constantinople. During the Byzantine empire, chariot racing was a huge deal—as were the team rivalries. Two factions called the Blues and the Greens, each rooting for a different-colored chariot, often let their rivalry erupt in violence outside the stadium. But in January 532, riots broke out not because of chariot racing, but because of a new ruling by the already unpopular emperor, Justinian. Soldiers gathered up the rebels and planned to execute the men in charge, but two of them escaped. The citizens learned that one of the escapees was a Green supporter, and the other a Blue. For once, the feuding fans had a reason to be united. At the next chariot race, they took up the victory chant usually reserved for the opposing teams (“Nika,” meaning “conquer”), and directed it against their emperor in opposition of the impeding executions. They swarmed out of the stadium, set fire to buildings, and literally carried another man onto the throne. Justinian considered fleeing the city, but eventually his wife rallied him to send his soldiers to quell the rebellion. After this, Justinian refrained from issuing any more harsh orders, and he became much more respected as an emperor. He never did choose a side in the Blues vs. Greens feud, though; in fact, chariot racing was forbidden altogether for the next five years.

Who let the dog out?

At the end of World War I, tensions were flaring between Greece and Bulgaria. The two nations had chosen different sides during the war, worsening the border disputes that had already been festering since the nations had gained independence from the Ottoman Empire. One day in October 1925, a Greek soldier was patrolling the Greek-Bulgarian border with his dog when the dog made a run for it, dashing across the border. The soldier ran after his precious pooch, and Bulgarian soldiers immediately began firing at him. When the skirmish at the border finally ended, the Bulgarians had killed three Greek soldiers. The Bulgarians apologized, claiming that they hadn’t realized that the soldier was just looking for his dog. But that wasn’t enough for a high-ranking Greek lieutenant, who insisted that the Bulgarians pay two million francs in reparations, and the Bulgarians refused. So the lieutenant ordered the Greeks to invade the Bulgarian village of Petrich, located right on the border, and they did. Nearly 50 people died, and it wasn’t until the League of Nations called for a ceasefire that they finally let sleeping dogs lie. Here are some more split-second decisions that changed history.

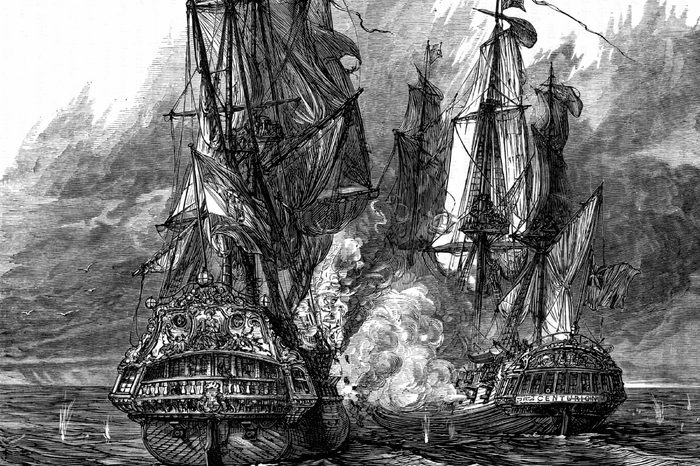

I’m all ears

If you can believe it, a war once started in Europe and spread to the American colonies over a seven-year-old face-slicing incident. The “War of Jenkins’ Ear“—yes, that’s the official name for it—began in 1738, when a British sea captain named Robert Jenkins strode into a Parliament meeting and dropped a severed ear on the table. He claimed that it was his own and that, seven years before, a member of the Spanish coast guard had sliced it off. Tensions had already been brewing between Spanish and English forces over Spanish seizure of British ships, as well as over the American colonies. The two nations couldn’t agree on the border between Florida (claimed by Spain) and Georgia (claimed by Britain). All it took was one ear for the tensions to escalate into all-out war, both in Europe and in the colonies. While neither side really won nor lost the ensuing conflict, France took advantage of the newly warring nations to team up with Spain against Britain and its ally, Austria, which both France and Spain viewed as far too powerful. So another war, the War of the Austrian Succession, began—and wouldn’t end until 1748—all because of a severed ear. Learn some more disturbing historical facts you’ll wish weren’t true.

Holy Toledo

The War of Jenkins’ Ear wasn’t the only conflict made worse by border disputes in the early United States. In 1787, Congress issued an ordinance designating lots of territory in the Midwest, including the states-to-be of Michigan and Ohio. The ordinance declared that the border would be a straight line from the southern tip of Lake Michigan to the shores of Lake Erie. The problem was that most of the maps of the time placed the tip of Lake Michigan further north than it actually was, leaving a single city—Toledo—in territory that both states had a potentially valid claim to. Ohio, which would become a state in 1803, insisted that the city was theirs, even though increasingly accurate maps showed that it technically belonged to Michigan. In the years that followed, both tried to assert their claim to the city, first with political measures and eventually with military threats. The two territories’ militias never actually clashed, but in September 1835, throngs of militant Michiganders swarmed the Toledo border, hoping to interrupt a planned court session where the governor of Ohio would officially lay claim to the land. The joke was on them, though—the Ohioans had secretly held the court the night before. The Michiganders called off their militia and accepted defeat, and Toledo remains a part of Ohio to this day. Learn about these states you’ve never heard of that were almost part of the USA.

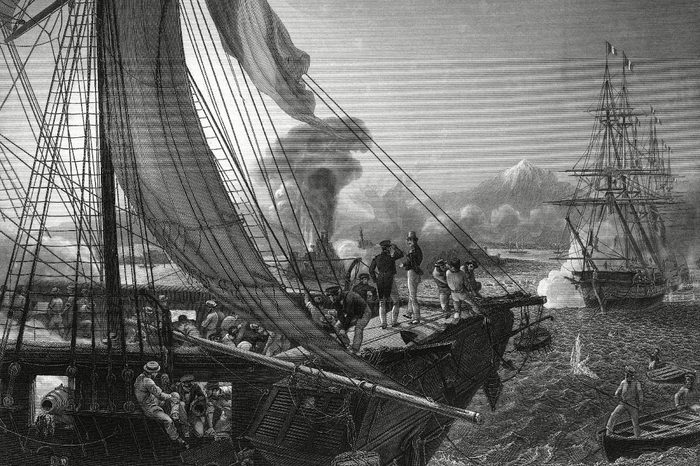

And you thought the Boston Tea Party was silly

Some fifty years after the Boston Tea Party, France and Mexico went to war over a pastry shop. The shop had been destroyed in a series of riots in Mexico City, and the chef, an immigrant from France, was upset he’d never been compensated. So he petitioned the French government for some money and waited…for ten years. Finally, French King Louis-Philipe decided to use the opportunity to get Mexico to pay back some of the debts they owed. So he demanded 600,000 pesos. The Mexican government, thinking a tiny pastry shop didn’t deserve that much, refused to pay. So the king sent a naval fleet and occupied the Mexican city of Veracruz. The infamous Mexican general-turned-dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna even came out of retirement to help fight. The conflict didn’t end until the British government intervened and demanded that Mexico pay. Because of the brief conflict, Santa Anna had regained enough support and confidence to lead a dictatorial political coup a few years later. As for the pastry chef, historians aren’t sure what happened to him.

The battle of the bucket

You could describe the “War of the Oaken Bucket” as a conflict fought for religious reasons, but what really started it was, indeed, a bucket. In 14th century Italy, spats were common between two city-states with differing opinions on who deserved to be the leader of the Christian church. Bologna believed it was the Pope, while Modena believed it was the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. After some informants revealed the location of a fort belonging to Bologna, Modenese citizens swarmed into the town and swiped a bucket full of money that the Bolognese had stolen in a raid of Modena. Bologna demanded its bucket back, Modena refused, and the Pope himself rallied thousands of his Bolognese supporters to attack Modena. The “War of the Oaken Bucket” that followed was only a single battle, but it was one of the Middle Ages’ bloodiest conflicts. Though the troops in Modena were vastly outnumbered, they overpowered the Bolognese in an underdog victory. As for the bucket, it is still on display in Modena to this day. Next, check out the most bizarre coincidences in history.