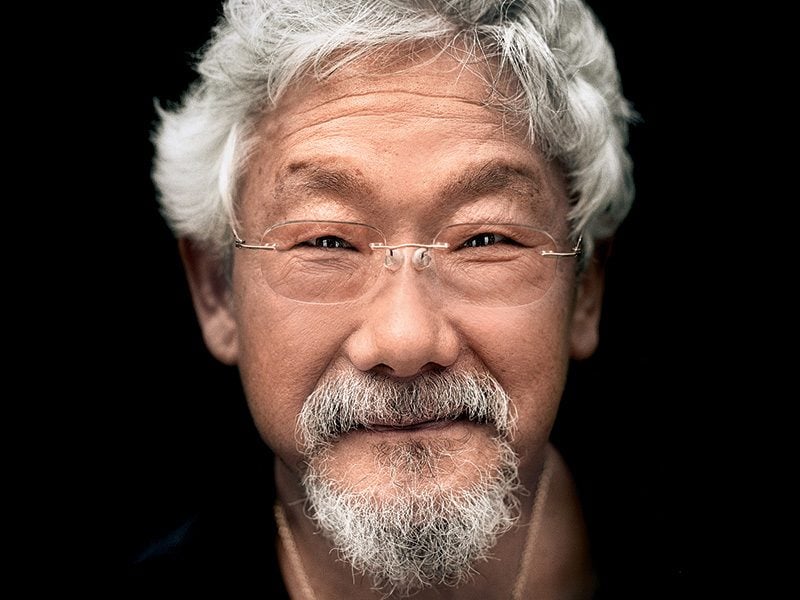

Why You Trust David Suzuki

The steadfast activist on hope for the future and why it comes down to older generations to shake things up.

Since 2006, David Suzuki has scored at or near the top of the Reader’s Digest Most Trusted Canadian poll. Today, at age 79, the celebrated broadcaster, scientist and activist describes himself first and foremost as an elder. For those who know him best as the level-headed host of CBC’s The Nature of Things, this Suzuki is a different kind of voice: more personal, more provocative, more passionate. Here, your Most Trusted Canadian Influencer of 2015 talks about his love of Kraft Dinner, the nature of our national identity and a plan for the environment in which we can all believe.

You’ve recently become a grandfather for the sixth time. What’s it like to welcome a grandchild into today’s world?

It’s very, very mixed. I’d never say it’s too late for the planet, but I’ve been around long enough to see where all the curves are going. When my two youngest daughters each got pregnant, my question was, “Look, you know what the situation is. Why are you doing this?” And what they said was interesting: that if you don’t have a child, you haven’t really made a commitment to the future. And that you’ll fight like mad for the future because you’ve made that commitment.

Is that sentiment part of your new book, Letters to My Grandchildren?

I thought that fatherhood was the greatest thing that ever happened to me. But having grandchildren is even better. Even in the best father-child relationship, there are times when one of you is angry with the other. You end up yelling or stomping out or whatever. With grandchildren, it’s different. They don’t see the flaws from living with you full- time. I was thinking back on my two sets of grandparents. Beyond simple exchanges, I never talked to them because they couldn’t speak English and I couldn’t speak Japanese. When they died, I felt terrible that I never got to ask the deep questions: Why did you come to Canada? What was it like when you came? Why did you stay, and are you glad? I’d like to leave some explanation about who I am and why I’ve done what I’ve done for my grandchildren.

How does it feel to be so trusted by Canadians?

I’m very honoured, but it does carry this huge responsibility. You know, I never really learned to cook, and when I went to college, one of the things I depended on was Kraft Dinner. To me, it’s comfort food. I remember I was shopping in Toronto and this woman came up and said, “You eat Kraft Dinner! I can’t believe it! How disappointing!” I thought, This is what you get from notoriety. But I’m just a human being, and I’m fallible.

Some people are afraid to call themselves environmentalists because of this “gotcha” kind of criticism. They feel they’re not “good” enough-they drive cars, fly in airplanes, don’t always eat organic food, and so on.

We don’t have the infrastructure to be ecologically neutral. Right now, the important thing is to share ideas and change minds, and the way I do that is by meeting with people or speaking. Unfortunately, in Canada, that means I have to fly, and flying generates a lot of greenhouse gases. Still, it doesn’t mean that we don’t need to try to minimize our ecological footprint. I did that by trying not to use a car, or when I needed to, I bought the first Prius [electric car] sold in Canada. We have a rule in our household: if you’re going to work or school, you take a bus or walk. We’ve reduced our garbage output to about one green bag a month, and I think we can reduce it further. But every time I jump in a plane, it negates everything else I do to live sustainably.

Why do you think it’s important that Canadians make these efforts to be environmentally sustainable when, as you say, we all live in an unsustainable system?

It’s an acknowledgement that these things matter. We have to at least try because we’re hoping to convince others that they all have to try, too. But there are different levels of contribution each person can make. In Canada, our highest level of contribution is our prime minister. He’s got to do the big things that we individually can’t do, like make a commitment to getting off fossil fuels and 100 per cent onto renewable forms of energy.

We live in an age of information overload. How can Canadians know whom to trust when it comes to environmental issues?

This morning I heard a corporate executive, a pipeline guy, saying, “We’ve got state-of-the-art technology, don’t worry.” And I’m thinking, What the hell else is he going to say? He’s a pipeline guy. Is he going to say, “We only detect five per cent of the oil leaks every year,” or “Once a spill happens, there’s not a lot we can do”? Why do we even bother listening to those people?

But you could say the same thing about environmentalists-that it’s just a propaganda battle between environmental groups and industry or the government.

I know that some people believe environmentalists are trying to scare you so they get more money. That’s just an astounding critique. Environmentalists are scrounging for dollars-an organization like the David Suzuki Foundation depends completely on ordinary people donating $30, $50 a year.

So there are easier ways to get rich.

A lot easier. The idea that people are going to somehow get rich by being environmentalists is laughable.

What sources of information do you rely on?

I read books. I go to Huffington Post, which I know is very middle-of-the-road. I read National Post columnist Andrew Coyne, even though I disagree with him a lot of the time, and I’m a big fan of Guardian columnist George Monbiot. The one source I read consistently is DeSmogBlog. I think they’re fantastic. But it’s a very sad time for media. That’s why the CBC is so important. Yet it’s being cut back so drastically-the one source showing Canada to itself is becoming toothless.

In 2012, you famously wrote that “environmentalism has failed.” Is your new Blue Dot campaign-to legally recognize our right to a healthy environment-a response to that realization?

I’d come to a point where I wasn’t exactly saying, “We’ve gotta give up,” but I didn’t know where to go next. To deal with our environmental challenges in a serious way, we have to modify everything. So how do you go about shifting society? There’s no magic bullet. But then environmental lawyer David Boyd came to us and said, “Do you know that more than 100 countries have some kind of protection for a healthy environment written into their constitution, and Canada doesn’t?” I immediately said, “That’s it!” A constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to a healthy environment shifts the conversation.

How have Canadians responded?

We originally thought we’d be on our way if we could get one community to approve a declaration of the Right to a Healthy Environment within six months. The city of Richmond, B.C., signed it three weeks after the Blue Dot tour started. We now have Montreal, Vancouver, Yellowknife and The Pas in northern Manitoba signed on, and dozens of other communities where people are trying to get a declaration passed. The campaign has taken off. What we’re saying is that if you really believe that clean air, clean water and clean soil should be among our highest priorities as a country, then you’ve got to get out there and get involved. You’ve got to fight for it.

We used to have a reputation for being a green country. Of course, it has never been that simple-we were criticized in the past for cutting down old-growth forests and overfishing, for example. And yet, it does seem that something has changed. Would you agree?

Yeah, that’s a part of Canada’s mythology. Well, the country was dragged reluctantly to that point by the environmental movement. Having said that, when the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro happened in 1992, opposition politicians, environmentalists and youth activists participated and were sponsored by the government. Canada was definitely committed to that process. What you see now is something fundamentally different. I just can’t get into the head of a person like our current prime minister. He’s not a builder. He is divisive.

Do you think Canadians have a special connection to our natural environment?

Over 90 per cent of Canadians say nature is critical to our identity and who we are. But the reality is that 80 per cent of us live in big cities, where the highest priority is having a job. We’ve come to accept that the economy is our government’s highest priority. The fact is, the average child today spends far less time outside than in front of a computer or iPad. We’re living in a world that is separated from nature.

What did nature mean to you as a child?

Being in nature was what we did. It was fun. Dad was an avid gardener, he loved collecting wild bonsai, and he was an avid fisherman. I never thought, Oh, we’re getting out in nature and I’m connecting with it. Nature was a part of who I was.

What changes in the natural world have you observed over the course of your own lifetime?

To me, one of the most profound ideas is shifting baselines-the way we are constantly changing our concept of what is normal. I was born in Vancouver in 1936, and when I was little, my dad and I would go to the mouth of the Fraser River and catch sturgeon. There used to be an annual salmon derby in English Bay, right off of downtown, with thousands of dollars in prizes. That was cancelled 30-odd years ago when there was nothing left to catch. The changes have been immense within my lifetime. In America they used to say, “That’s the price of progress.” We need a different definition of progress.

Such as?

A way of living a healthy, happy life, within a healthy environment and a community that gives us meaning and dignity.

What does time spent in nature mean to you now?

To be honest, I’m at an age where a lot of things-like backpacking, which I love-aren’t as easy as they once were. When you’re younger, you revel in it-if it rains, what the hell, you live with it. Now it’s, Oh, God, I’m going to be cold. And my wife has had a severe heart failure, and we can’t go anywhere where we don’t have access to medical care, so long, wild trips probably aren’t going to happen anymore. But I still call nature my medicine. I love getting out where you don’t have to worry about, “Oh, another voice mail,” or all the email you’re going to have. We’ve complicated our lives so much, it’s unhealthy.

We’re in an election year. What topics would you like to see on the political agenda?

We’re facing a catastrophic moment with climate change, and we’ve seen this crazy plunge in the price of oil. It’s an opportunity to really talk about the energy future of this country, and we’re not. What we need to do is have more Canadians engaged in the political process. I’m telling parents, you’ve got to be eco-warriors fighting to make the future of your children a political issue. You’ve got to force candidates to make a statement about where young people’s futures lie in their political agendas. We’ve got to reclaim democracy.

It seems to me that your public persona is evolving. You’re not just the gentle scientist from The Nature of Things I knew growing up-you seem angrier.

I think it’s passion more than anger. I never apologize for being passionate. But it is interesting. I am getting angrier because I’m speaking now as a grandfather and an elder. I think it’s our job to be pissed off! We have a very important role because we don’t have to worry about getting fired or losing a promotion or a raise. Elders are free to speak the truth from our hearts. There has never been a time to be more frightened and angry than now, so if that’s the way I’m perceived, good. I embrace it!

So you’re not planning to fade from the public eye any time soon.

My wife has finally got me to stop saying “retirement.” She says, “You’re doing what you want to do and what you enjoy doing, and you believe in what you’re doing-what better thing could you do with your life?” I’ll keep going as long as I can.

J.B. MacKinnon is co-author of The 100-Mile Diet. His most recent book is the national bestseller The Once and Future World: Nature As It Was, As It Is, As It Could Be.